Suicide Amongst Second-Generation Alevi Boys in the UK

The social context of Alevi people in the UK

Alevi migration to the UK in meaningful numbers dates back to the 1980s, post the military coup in Turkey, when many left the country to escape violence and torture under the junta regime. The number of migrants peaked in the late 1980s/ early 1900s when they arrived in the UK as political refugees. They came mainly from the rural areas of provinces such as Maraş, Sivas, Malatya, Kayseri, and Antep, which are renowned for the massacres and pogroms against Alevis. The main ‘push factors’ for Alevis to flee Turkey at this particular time include fear of further massacres associated with the rise of ultra-nationalist and Islamic fundamentalist groups and guerrilla warfare between the Kurdish Workers’ Party (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, PKK) and the Turkish state. The main pull factors attracting them to the UK were the absence of a visa requirement, knowing someone already settled in London, and hopes of a better education and life for their children (Cetin and Jenkins, 2024).

The first generation Alevis lived in London boroughs such as Hackney, Haringey and Islington, working hard to create a life for their families and were free to practice their religion, which gave them a sense of pride. They established themselves as a self-contained and efficient ethno-religious community, living in the same neighbourhoods and social housing, working in textile factories, catering, corner shops and shared employment. By the early Nineties, they mobilised under political, cultural and religious community centres, attending weddings and cultural events organised by the community centres. This was a type of integration within itself rather than into mainstream society. This integration is described as ‘segregated integration’ (Cetin 2013), which was underpinned by a lack of English language fluency and little engagement with other communities culturally. However, the situation for their second-generation children was different. By second-generation, I mean children of first-generation parents who were either born in the UK or educated here, experiencing the British way of life and values (Cetin, 2016). They were going to school and integrating with others from diverse backgrounds, learning English and dreaming about getting rich quick without working as hard as their parents. The incidence of the second-generation boys killed by suicide was a complete shock to the community, as it had never been an issue before. The next section follows their journey towards a suicidal outcome.

The ‘deaths by suicide’ of second-generation Alevi boys

When I interviewed a dede (religious leader), he maintained that Alevism does not permit suicide under any circumstances:

“In Alevism, suicide and murder are treated as the same. It is equivalent to the killing of another living being. Committing suicide is a sign of not being capable. You are not given a life to take it away.” (Dede, in London).

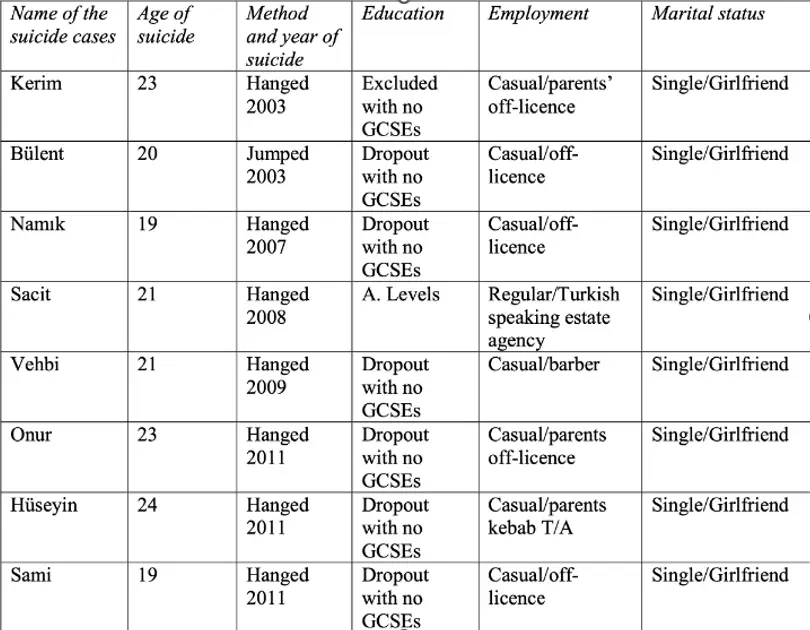

The idea of death by suicide is a recent development which takes the opposite view and shifts blame away from the person taking their own life to understand the individual, social and other factors leading to this outcome (Cetin 2022). Researching suicide is a highly sensitive topic, and understanding what led to it is complicated by the person not being able to explain their motivation, and the obvious distress of those most affected. My research aimed to make sense of the experience of death by suicide through talking to family members, friends and the wider community. I spent time at the community centre and attended some of the funerals too. Gradually, Alevis were aware that I was researching this issue and would talk to me. I interviewed family members and friends of eleven of the second-generation boys who died by suicide, only doing so with their permission. I also conducted interviews with three Alevi young men who had attempted suicide. Some reported a sense of relief at being able to tell their stories, as they felt others were blaming them. I have protected the identities of the boys by changing their names and leaving out details that might result in their being recognised. My research identified similar characteristics in their lives, which might explain their journey towards death by suicide (see the table in picture *All the names have been anonymised)

I will explain how these factors impacted the second-generation Alevi boys. Most Alevi children made their way in an unfamiliar society whilst fulfilling their parents’ expectations of succeeding in school and work. Through learning English, children often interpreted for their parents in official settings, and some took advantage of this power over their parents to mislead them about what was happening in and outside of school. This role reversal was an important contributing factor for those who followed a downward spiral into the rainbow underclass with high suicide risk. One boy explained how he gained power over his parents, as the quote below shows, and it led to him losing respect for them:

“I used to fake my mum’s signature and return it to the school […] One day, I came home and there was a letter to inform my parents that I was expelled from the school for a few days. I told my mum that the school is taking us on a trip and I need to take thirty pounds with me. She said OK.” (Burhan, in London).

Most Alevi children succeeded in primary school, but some found secondary school more challenging. Underachievement at school had several causes and consequences, especially for boys. There was little support available for students who were underachieving, and their parents could not assist them because they lacked understanding of the education system and the language. In school, boys typically experienced racism and inter-ethnic tensions, often joining school gangs for protection, and gradually losing faith in education as a fair system. This disconnection contributed to them dropping out or being excluded from school. For boys in particular, underachievement could be the main tipping point prompting a downward spiral into the ‘rainbow underclass’.

Portes et al (2005) describe the ‘rainbow underclass’ as associated with underachievement, inter-ethnic conflict, involvement in gangs, a crisis of masculinities, troubled family/ personal relationships and risk of suicide. Durkheim, a C19th sociologist wrote his famous study Suicide in which he describes society as balanced by forces of integration (family, education, work, for example) and regulation (law, police, army etc) and when this balance is disturbed, it creates instability leading to different suicide outcomes depending on whether there is too much or too little regulation or integration. Anomic suicide occurs when there is too little regulation, giving rise to a sense of disconnection or anomie, which creates conditions in which suicides might occur (Cetin 2016). For Alevi youth, their religious identity significantly influences their experiences. Teachers and peers frequently assume they are Turkish and Sunni Muslims because they come from Turkey. This assumption generates tension with other Muslim students, as Alevis would describe themselves as “sort of Muslim” but without following traditional Muslim practices. Consequently, they were sometimes subjected to bullying (Jenkins and Cetin, 2018). Alevi boys experienced tensions at home if they were failing at school and tensions at school with teachers and peers due to racism, inter-ethnic and religious tensions, leading to a loss of respect for schools as a route to a better future. Instead, they were influenced by gang members having smart cars and lifestyles and began to see gang life as a better means of getting rich, achieving power over others and respect, not available to them through legal means. Realistically, their involvement in gangs was low level and would not fulfill their dreams of wealth, which generated an anomic situation where the boys felt trapped in all areas of their lives. The shattering of future dreams and/ or a breakdown in relationships with their family or girlfriends could be the final tipping point in their deaths by suicide.

The wider impact of the deaths by suicide on the community

Understandably, the impact of the deaths by suicide on families and the community was devastating. In the surrounding panic about this suicide pandemic, parents and girlfriends were blamed for not preventing the boys’ deaths by suicide. Some parents were distraught that they had come to the UK for a better life for their children and instead lost one to suicide. Other parents talked about how once their children went to school, they listened more to their friends than their parents. For example, one father said:

“It is sad that we Alevi people could not protect our children from a bad environment. We as a family do not have any influence or control over our children because the child goes to school and makes a lot of friends who tell him to do bad things. At that age, the child listens to them, not me.” (Hasan interview in London)

This quote reflects that, unlike the more segregated first generation, these Alevi boys drifting into the rainbow underclass, positioned themselves on the margins of both the Alevi community and mainstream British society and were beyond help.

The community liaised with police, social services, medical doctors and other professional services to make sense of what was happening and to prevent further losses. Representatives from the community centre felt that Alevi youth had a negative identity because they did not know much about their religion, and felt marginalised by others because of it. Based on my research, generating a greater understanding of why boys were being killed by suicide, the England Alevi Cultural Centre and Cemevi (IAKM-C) committee invited the University of Westminster to assist with finding solutions. Following discussions with young people, they said they learnt about other religions at school, but nobody knew about theirs. Many could not describe their religion because it was suppressed in Turkey, and they wanted Alevism lessons to be part of the religious education curriculum. With the importance of education as a tipping point into the rainbow underclass and the disconnection Alevis felt in school, the Alevism lessons presented an opportunity of transforming a negative identity into a positive one (Jenkins & Cetin, 2018). Indeed, the Alevism lessons proved transformative because Alevi youth felt more included in schools and understanding more about their religion made them prouder of their identity. The subsequent reduction of suicides of second-generation boys cannot be causally connected to the lessons but it achieved positive changes in schools, increasing the acceptance of Alevism as a distinct religion.

Conclusion

My sociological investigation into the deaths by suicide among second-generation boys has identified key factors these individuals faced prior to their suicides. A factor common to all cases was educational underachievement, which marked the beginning of their journey into the ‘rainbow underclass’. As of today, there is no suicide pandemic among Alevi boys in the UK. The deaths by suicide occurred at a time when parents were adjusting to life in the UK and were unaware of any pressures their children experienced. Most first-generation parents are grandparents now and the second generation of Alevis are now parents with a deeper understanding of education and British society. This shift has fostered stronger connections with their children and enhanced transnational relationships. While it is difficult to claim that the suicides have completely ceased, there is a significant decrease compared to previous years. Additionally, the Alevi community is more established and actively engaged in projects aimed at raising visibility and improving conditions for Alevis. Initiatives such as Alevism lessons and the inclusion of Alevism as a recognised religion in the 2021 Census have fostered a sense of pride and underscored the community’s value as members of a multicultural society.

Cetin, Umit ve Celia Jenkins. 2024. “British Alevi-Kurds: Politics, Education, Religion and Integration Strategies in the UK and Their Transnational Impact.” İçinde Routledge Handbook of Turkey’s Diasporas, editörler Zekiye Ayça Arkılıç ve Banu Senay. London: Routledge.

Cetin, Umit. 2020. “Unregulated Desires: Anomie, the ‘Rainbow Underclass’ and Second-Generation Alevi Kurdish Gangs in London.” Kurdish Studies 8 (1): 202-227. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004700369_011.

Cetin, Umit. 2017. “Cosmopolitanism and the Relevance of ‘Zombie Concepts’: The Case of Anomic Suicide amongst Alevi Kurd Youth.” The British Journal of Sociology 68 (2): 145-166.

Cetin, Umit. 2016. “Durkheim, Ethnography and Suicide: Researching Young Male Suicide in the Transnational London Alevi-Kurdish Community.” Ethnography 17 (2): 250-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/146613811558658.

Cetin, Umit. 2014. Anomic Disaffection: A Sociological Study of Youth Suicide within the Alevi Kurdish Community in London. Yayımlanmamış doktora tezi, University of Essex, United Kingdom.

Durkheim, Émile. 1996 [1897]. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Çev. John A. Spaulding ve George Simpson. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, Celia ve Umit Cetin. 2018. “From a ‘Sort of Muslim’ to ‘Proud to Be Alevi’: The Alevi Religion and Identity Project Combating the Negative Identity among Second-Generation Alevis in the UK.” İçinde Contested Boundaries: Alevism as an Ethno-Religious Identity, editör Celia Jenkins ve diğerleri, 92-105. London: Routledge.

Portes, Alejandro, Patricia Fernández-Kelly ve William Haller. 2005. “Segmented Assimilation on the Ground: The New Second Generation in Early Adulthood.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (6): 1000-1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870500224117.