Splendor and Light of God: Sun Worship Among the Raa Haq Followers and Their Neighbors

The Splendor and Light of God: The Sun in the Beliefs of the Raa Haq Community[1]

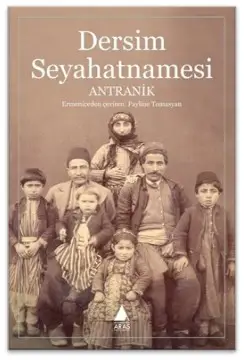

In 1888, an Armenian resident of Dersim, Andranik Yeritsian, traveled from Kiğı (Kurdish: Gêxî; Bingöl Province) to Central Dersim. His travel notes were published in Tiflis in 1900 under the title Dersim Seyahatnamesi. Like many of his contemporaries, he referred to the followers of the Raa Haq faith as Kızılbaş. He said that their religion had developed from ancient beliefs and traditions. The sun, moon, and stars were worshipped.[2]

Naide Duymaz, a member of the Raa Haq community, reports on their deep connection with nature: “My father woke up before sunrise, washed his face, and turned toward the sun. He ran his hands over his face and said the following prayer: ‘Oh God! First help the poor, the wolves, and the birds who are hungry and in need, and then help us!’[3]

Dr. vet. M. Nuri Dêrsimi (1893-1973), who also belonged to the Raa Haq community, wrote in his book ‘Dêrsim in the History of Kurdistan’ that it was the duty of every Dêrsimer to pray ‘Hode (Persian: Khoda, Kurmancî: Xwede, Kirmanckî: Homa). For the Raa Haq community, the sun is God’s glory or God’s light. ‘Bê asm u roz dina tariya (A world without the moon and sun is dark),’ quoted from the cleric and poet Sey Qajî.”[4]

Many people celebrate the beginning of spring, which brings new hope, peace, and reconciliation to the world. The spring equinox on 21 March also has a special meaning for the Raa Haq community. This day is celebrated as the birth or victory of light over darkness. In Raa Haq teachings, light is considered the source of all existence. The festival is called Xewt u Mal (Seven of the Little Livestock) and is celebrated as a festival for nature. In Dersim, the welcoming of spring is also called Qere Çarseme (Black Wednesday).

In Dersim mythology, the number 7 symbolises the seven colours of sunlight. This festival also involves a religious gathering of the community at sacred rivers. The faithful say prayers, share gifts with those in particular need, and light Çıla (candles) during the gathering, while the Pîr (cleric) recites a ‘Gulvang’. The lighting of candles represents the awakening of light. The Semah ritual is then performed with mystical poems.

Ancient Sun Gods and Goddesses: Elias – Helios – Sol – Mithra

In the Old Testament, and consequently also in Islam, Elias (Greek) or Eliyah (“Yahweh is my God”; Hebrew) is considered a messenger of God and a prophet. Elias predicts the death of King Ahab and Queen Jezebel, who later die. Elias, on the other hand, is carried up to heaven at the end of his life by a chariot of fire with fiery horses in a storm wind. In Greece, especially on its islands, the highest mountain peaks are named Profitis Ilias (modern Greek: Προφήτης Ηλίας, ‘Prophet Eliyah’). But there are also numerous peaks with this name on the Greek mainland, 69 of which are over 1000 meters high[5], because the prophet is considered the saint of the mountains. In the Old Testament, Mount Horeb was the refuge of the prophet Eliyah from persecution by Jezebel, the wife of the Israelite king Ahab (9th century BC).[6] From there, Profitis Ilias was borrowed as a name for high peaks.

However, it is not only phonetically that the Greek name Elias is reminiscent of Helios, the ancient Greek sun god, but also through his attribute, the sun chariot drawn by four fire horses (Pyrois, Aeos, Aethon, and Phlegon). “According to some accounts, the worship of Eliyah effectively filled the gap left by Zeus, the ancient Greek god, the cloud gatherer, lord of the sun, lightning and winds, and master of time; Zeus was also celebrated around the same time as the feast day of Eliyah. So, according to popular tradition, the fact that the Prophet Eliyah is worshipped on mountaintops is related to some extent to the ancient Greek belief system. This Old Testament prophet and Church saint was quite naturally associated with the sun (Helios in Greek), as the sound of his name was similar to the word for the life-giving, celestial body.”[7]

Helios belongs to the generation of Titans, the older family of gods before the Olympian Zeus. He is the son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia and brother of the dawn (Eos) and the moon (Selene). He is depicted as a handsome god with a shining halo, which underlines his divine connection to the sun. Helios crosses the sky in his sun chariot and symbolises knowledge and clarity with his light. In Roman mythology, he is known as Sol and was later merged with other gods of light such as Apollo. Since Helios travels across the world every day, he is all-seeing. No misdeeds remain hidden from him, which also makes him a witness to all events. Literarily, Helios plays a role in Homer’s Odyssey, where he shows off his cattle, and in myths such as the story of his son Phaethon, who was unable to master the sun chariot.

In the Roman Empire, the sun god Sol (Latin for “sun”) was considered the highest and most powerful god. However, his worship competed with the Oriental cult of the Indo-Iranian deity Mithras, which was particularly popular among soldiers. The cult of Mithras never became the Roman state religion and did not merge with the worship of Sol, even though the followers of Mithras also called their god Sol invictus (“unconquered sun”). The birthday of the Sol Invictus falls on 25 December. This date was later elevated to Christmas. In 274, Emperor Aurelian elevated the cult of Sol Invictus to the status of a Roman imperial cult.

However, by 8 November 392 at the latest, when Emperor Theodosios I issued his religious edict, sun worship was illegal in the (Eastern) Roman Empire. Nevertheless, there were still numerous worshippers of Sol in the 5th century. Around the middle of the 5th century, Pope Leo the Great rebuked the custom, still widespread among “simpler souls” in Rome at that time, of considering 25 December worthy of worship only “because of the rising of what they call the new sun.”[8] Moreover, the same Roman bishop also lamented the continuing worship of the sun by many Christians, which proves that the Roman sun cult found its way into Christianity; according to Pope Leo, it was common for believers to turn around after ascending to St. Peter’s Church to bow down before the rising sun (serm. 27,3f.).

In Norse mythology, the gods formed the sun from a spark and placed it in a chariot. The goddess Sol drives the chariot across the sky, pulled by the horses Alsvidr and Arvakr. The team is constantly pursued by the wolf Skalli (Skoll). On the day of the apocalypse (Ragnarök), the wolf will devour the sun.

Quran

In the Quran, the prophet Eliyah is called Ilyās (إلياس), and in the Arabic translation of the Bible, Īliyā (إيليا). He is mentioned in two suras: In Sura 6:85 corp, the prophet is named among a series of “righteous” people: “We guided Zacharias, John, Jesus, and Īliyā -each of them is among the righteous.” The idea of righteousness is taken up again in Sura 37:123-132 corp. In addition, God’s direct speech recounts the confrontation with the worshippers of Baal: ” Īliyā was [is] truly one of messengers [of God]. When he said to his people, ‘Will you not be God-fearing? Will you pray to Baal and abandon the best Creator [one can imagine], [the one] God, your Lord and the Lord of your forefathers?’ They called him a liar. […] And we left him [as a legacy] among later [generations] the blessing: ‘Peace be upon Īliyā!’ Thus we reward those who are pious. He is [one] of our believing servants.”[9]

Sun Gods of the Armenians

Little is known about pre-Christian Armenian mythology, which was apparently highly syncretistic. It was of Indo-European origin and was later strongly influenced by Mazdaism (e.g., the deities Aramazd, Mit(h)ra, and Anahit) and Assyrian traditions. Urartian, Mesopotamian, and Greek beliefs and deities were also adopted.

The sun is called Areg, Aregakn, or Arev in Armenian, which also means life. Xenophon (Anabasis IV, chap. 5) attests that the Armenians sacrificed horses to the sun god because horses were considered sacred to their sun god. In Armenian mythology and fairy tales, fire horses very often appear as attributes of heroes. Areg (Arev) or Ar is thought to have been the original or oldest Armenian sun god, comparable to the Mesopotamian Utu[10]; he was probably also called Ara. This god was probably mentioned on the Door of Mher near the Urartian capital Tushpa (Armenian: Tosp; Van) as Ara or Arwaa. The linguist Heinrich Hübschmann and, following in his footsteps, the linguists Martin E. Huld and Birgit Anette Olsen suspect that the word arew is related to the Indian name Ravi, which also means “sun.”[11]

“The ancient sun cult of the Armenians, which under Persian influence merged with the cult of →Mihr and later with that of →Vahagn, persisted for a very long time even after Christianization. The sun worshippers of that time were called ‘sons of the sun’ (Armenian: ‘Arevordik’). (…) The ancient Armenians are said to have sworn by the stars, but especially by the sun. (…) The eighth month of the Armenian calendar is called ‘Areg’. ‘Areg’ is also the name of the first day of each month.”[12]

Merzifon (in the Ottoman kaza of the same name) was home to one of the last communities of Armenian Zoroastrians – known as Arevordik (‘children of the sun’), who are believed to have been killed in the genocide between 1915-17. In the town of Merzifon, in the early 20th century, the Armenian quarter was known as “Arevordi.” Furthermore, a cemetery outside the town was known as “Arevordii grezman,” and an Armenian owner of a nearby vineyard was named “Arewordean,” in other words, Armenian for “Arewordi-son.”[13]

The name of the sun god Areg is still a popular first name for girls and boys among Armenians today, as is the first name Ara (only for men). Similarly, the greeting “barev” refers to the sun god, as it is a contraction of the words “bari” and ‘arev’ meaning “good day” (literally “good sun,” “good life”).

֍ A symbol of the sun and eternity that has been omnipresent in the Armenian settlement area throughout history and remains so today is the Arevakhach (literally “sun cross”). It can be found on gravestones and cross stones, on the walls of secular and sacred buildings, and forms the Armenian national symbol. The sun cross symbolizes goodness, life, fire, fertility and birth, progress and development. The sun cross exists in a clockwise and a counterclockwise version; the former is associated with activity, the latter with passivity. Similarly, the clockwise version is found on baby cradles when a boy is expected, while the counterclockwise version is associated with a girl.

Sun and Fire Worship Among Zoroastrians

The religion of Zoroastrianism or Zarathustrianism (also: Mazdaism or Parsism) is named after its founder Zarathustra. The religion of Zarathustra, which is based on very ancient Indo-Iranian traditions and lore, originated between 1800 and 600 BC. Its origins are disputed. It spread from around the 7th to the 4th century BC in the Iranian cultural area (from eastern Asia Minor and Mesopotamia to Persia and Central Asia). The current number of believers worldwide is estimated at up to 150,000, living as minorities in Iran (up to 25,000), India (up to 60,000, known there as Parsis), and North America (approx. 22,000).

Zoroastrians do not worship the sun itself, but see it as an important, bright, and pure element that represents the god Ahura Mazda and divine truth (Asha). At the heart of their faith is the worship of Ahura Mazda and the pursuit of truth and order, symbolized by the light of the sun and the purity of fire. However, the central element of worship is the sacred fire in the fire temples, which is identified with truth as a pure and purifying force and thus represents a connection to the divine light of the sun. In Zoroastrian cosmology, the sun is a symbol of good, light, and life, while darkness and destruction are associated with evil.

Conclusion

In the cosmology of almost all people, the sun plays a prominent role as a deity -usually conceived as male- or as a symbol of God. A common attribute of sun gods, as well as of God’s messengers or prophets, is the sun or fire chariot and the accompanying fire horses. As the ancient Iranian belief in particular illustrates, the cult of the sun is associated with that of fire, whose light is attributed to the here and now and the world of good. These ideas are also found in the beliefs and rituals of the Alevi Raa Haq community of Dersim, for example, in the attitude toward the sun in morning and evening prayers or in the spring festival of the equinox Xewt u Mal.

Halsberghe, Gaston H. 1972. The Cult of Sol Invictus. Études préliminaires aux religions orientales dans l’Empire romain 23. Leiden: Brill.

İshkol-Kerovpian, K. 1986. “Mythologie der vorchristlichen Armenier.” In Wörterbuch der Mythologie, hrsg. Hans Wilhelm Haussig. Abt. I: Die alten Kulturvölker, Bd. IV: Kaukasische Völker, 59-160. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett Verlag.

Martirosyan, Hratch. 2014. Origins and Historical Development of the Armenian Language. Leiden: Brill.

RAA HAQ – The Alevis in Dêrsim. 2017. Alevitentum (Platform for Alevis), 18 July 2017. https://raahaq.wordpress.com/2017/07/18/first-blog-post/ (accessed 15 September 2025).

Richter, Siegfried G. 1997. The Ascension Psalms of Heraclides: Studies on the Ascension of the Soul and the Mass for the Souls of the Manichaeans. Languages and Cultures of the Christian Orient 1. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag.

Russell, James R. 1986. “Armenia and Iran III: Armenian Religion.” In Encyclopædia Iranica, ed. Ehsan Yarshater, vol. II/4, 438-444. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul.