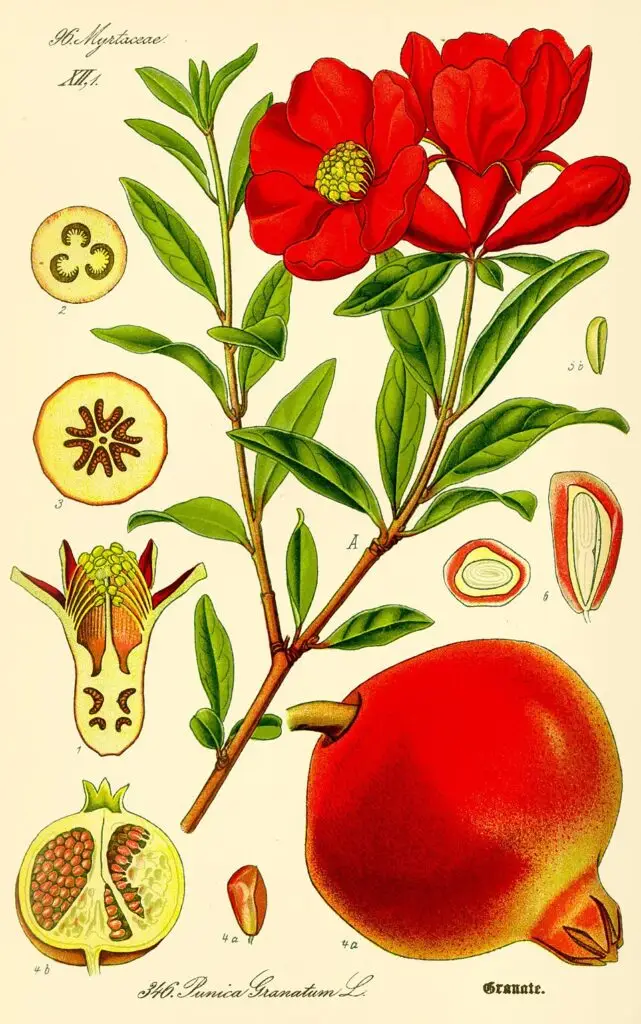

Pomegranates: Ambivalent Symbol of Life and Death

The Yarsan religion, which is closely related to the Alevi faith and philosophy and, most of all, the Raa Haqi community, attributes special significance to pomegranates. It is a belief based on nature, society, nature and social laws and traditions. To show their respect and closeness to nature and society, the Yarsanis, who celebrate all four seasons, celebrate the products they obtained from nature through these feasts. Autumn means Pomegranate Festival for the Yarsanis.

Mythological and Cultural Meanings [1]

The pomegranate was originally the symbol of the Semitic mother goddess Atargatis (Greek; Atar’ata (Aramaic), as the Greco-Roman form Dea Syria), who was particularly revered in northern Syria, as well as the ancient Iranian goddess Ardvi Sura Anahit(a). Anahita is the goddess of water, and all the water on earth springs from her heavenly source. She is also the goddess of maternal fertility and ensures healthy offspring for humans.

The ambivalence of the pomegranate as a symbol both of life and death lies in its physic features: The pomegranate’s seeds are often seen as a symbol of life, as they are a source of nourishment and sustenance. However, the fruit’s aril, which surrounds the seeds, is often seen as a symbol of death, as it is a bitter and difficult to digest. In some cultures, the pomegranate is seen as a fruit that only grows in the underworld, or in the presence of death. For example, in ancient Greek mythology, the pomegranate was associated with the gods Hades and Persephone. Hades kidnapped Persephone and took her to the underworld. The father of the gods, Zeus, decided that the girl could return to her mother Demeter, if she had not eaten anything in the underworld. Shortly before her return, Hades pressed six pomegranate seeds into her mouth. Since she had now eaten something in the underworld, she had to rule with Hades for a third of the year and was allowed to spend the other two thirds with her mother Demeter.

In Persian culture, the pomegranate is often associated with death due to its symbolism in the ancient Mazdaist religion. According to Mazdaist mythology, the pomegranate was said to be the fruit of the dead, and it was believed that this fruit would only grow in the underworld. This mythological significance has been passed down through generations, solidifying the pomegranate’s connection to death in Persian culture.

The pomegranate was also significant to the three Abrahamic religions, not only as the fruit of paradise.

The Old Testament presents the pomegranate in a generally positive light, as it is considered one of the seven significant fruits with which the Promised Land Israel was blessed.[2] In his Song of Songs, King Solomon compares the people of Israel to a woman who is in love with her husband (representing God): “Your forehead behind your veil (shines) like a pomegranate…” (Song of Songs 6:7). The author of the Song of Songs repeatedly refers to this fruit in his vivid imagery to praise beauty: “You have grown like a garden of pomegranates with choice fruits, with cypress flowers and lilies” (Song of Songs 4:13).

The Talmud also uses a pomegranate metaphor when referring to a particularly attractive person, comparing it to a cup filled with ruby-red pomegranate seeds (Baba Metzia 84a).

Pomegranates symbolize the fertility of the land of Israel (Num. 13:23; Deut. 8:8). In the days of the ancient temples in Jerusalem, the Kohen Gadol – the high priest who served in the temple – wore a magnificent robe decorated with 72 golden pomegranates (interspersed with 72 golden bells) hanging from the lower part of his robe (Exodus 34:34). These were reminiscent of a series of carved pomegranates near the massive carved pillars of the temple.[3] The Tanakh describes the architecture of the First Temple built by Solomon: “He made pillars, two rows around, to cover the capitals with pomegranates” (1 Kings 7:18).

According to 1 Sam 14:2 Lut, King Saul lingered under a pomegranate tree. Finally, the pomegranate tree is also found in the prophets Joel 1:12 Lut and Haggai 2:19 Lut. According to a Jewish myth, the (perfect) pomegranate has 613 seeds, the number of Jewish mitzvot (commandments) contained in the Torah according to the Talmud.[4]

Granada

“When Jews first settled outside the land of Israel, they often took pomegranate seeds with them and planted them in their new homes. Such a group of Jewish settlers founded a city in southern Spain in ancient times.

The original name of this city is no longer known today, but when the Moors invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 711 CE, they came across this Jewish settlement and, seeing the many pomegranate trees belonging to the Jews, gave it an Arabic name meaning “pomegranate”: Gharnata al Yahud – “pomegranate trees of the Jews.” This name stuck and eventually evolved into Granada.[5]

The Christian Order of the Merciful Brothers has a pomegranate with a cross as its emblem. The order was founded in Granada, which has the pomegranate in its coat of arms; moreover, the pomegranate has become a symbol of Jesus in the Catholic Church. The city of Granada, the province of the same name, many of its towns, and parts of the Spanish coat of arms feature the pomegranate, which represents the ancient Kingdom of Granada after its conquest by the Christian rulers of Spain. The flag of Spain shows the national coat of arms and therefore also a pomegranate (at the bottom center of the coat of arms). The surrounding countryside is still an important growing area today.

The Pomegranate in the Quran

The pomegranate (Arabic: Ar-Rumman, after the city of Rimmon near present-day Hebron) is mentioned in three places in the Quran: 6:99, 6:141 and 55:68. In verse Ar-Rahman (“The Merciful”), 68, God speaks of fruits that people will find in paradise. The pomegranate is an example of the good things created by God. The Quran describes both earthly fruits and those of paradise: “And it is He who sends down water from the cloud, and We bring forth thereby all kinds of growth; with which We bring forth green plants, from which We produce grain in rows, and from the date palm, from its flower clusters, (sprout) hanging clusters of dates, and gardens with grapes, and the olive and the pomegranate – similar and dissimilar. Look at their fruit when they bear fruit and their ripening. Truly, in this are signs for people who believe.” (The Cattle, 6th Sura, 99)

Jannah, the abode of the righteous after death, is a garden “rushing with streams” (Sura 2, 25) in which numerous fruits grow. Among the plants are palm trees, grapevines (2, 266; 17:91; 36:34) and pomegranates (55:68). “In both there will be fruits, and dates and pomegranates.”

In Christian symbolism, the pomegranate can stand for the Church (Greek: Ekklesia), as the community of believers. However, this ancient symbol of fertility also symbolizes the abundance of martyrs and mysteries in the Church. The hard, red skin of the fruit was associated with the Church stained red with the blood of Christ and the martyrs (cf. e.g. Bede in Cant. expos. 4 = PL 91,1145). The many sweet seeds represent the unity of the members of the Church (cf. e.g. Ambr. Iac. 2,1,3 = PL 14,646). The invisible but tasty seeds were also used allegorically, for example to refer to the hidden virtues of a soul consecrated to God (cf. Bede in Cant. Expos. 6,24 = PL 91,1180). The pomegranate also symbolizes the fact that creation is contained in God’s hand or providence.[6] It is also the symbol of the priesthood because it bears rich fruit in its hard shell (= asceticism of the priesthood). Because of this symbolism, the pomegranate appears in numerous medieval panel paintings.

Pomegranates on New Year’s Day

On the Jewish New Year’s holiday “Rosh ha-Shana,” Jews around the world recite a blessing over pomegranates before beginning their festive meal. Since pomegranates are associated with a life full of mitzvot, it is traditional to express the wish that our coming year may be as full of mitzvot and good deeds as a pomegranate is full of seeds. On Rosh Hashanah, believers give an account of their actions before God and commit themselves to repentance. It is the only holiday that is celebrated for two days, both in the diaspora and in Israel.[7]

The Armenian Apostolic Church adopted some Jewish rituals and institutions in its early days. Pomegranates also play a role in New Year celebrations: Armenian Christmas in Istanbul includes the fasting dish topik, made from puréed chickpeas, potatoes, and stewed onions, delicately seasoned with sesame paste, allspice, black pepper, and cinnamon, as well as pomegranates.

During the New Year’s service, the Armenian Apostolic Patriarch of Istanbul blesses thousands of these fruits before they are distributed to the faithful.

Pomegranates in Ahl-e Haqqi Belief

In Alevi belief, the pomegranate (Farsi: anar; Turkish: nar) is a multifaceted symbol associated with various aspects of faith, nature, and social harmony. It is often linked to the →Yarsan philosophy, which is very close to the Raa Haqi faith, and symbolizes righteousness, fertility, and abundance. The pomegranate’s symbolism also extends to love, passion, and eternity, making it a significant element in Alevi culture and rituals:

Symbol of Righteousness and Abundance: Like in Jewish tradition, the pomegranate’s numerous seeds can be seen as representing the multitude of good deeds and commandments. This aligns with the Alevi emphasis on righteous living and community well-being.

Connection to Nature: The pomegranate, with its vibrant color and nourishing fruit, is a natural symbol that resonates with the Alevi reverence for nature. It embodies the bounty and beauty of the natural world, which is central to Alevi beliefs.

Symbol of Love and Passion: In some contexts, the pomegranate is associated with love and passion, suggesting a connection to the emotional and spiritual depth of human relationships.

Eternity and Continuity: The pomegranate’s longevity and the fact that it continues to bear fruit year after year can also symbolize eternity and the continuity of life and faith.

Nar Bayrami: The annual Nar Bayrami (Pomegranate Festival) is a key example of the pomegranate’s cultural and social significance. It celebrates the fruit’s importance in Alevi life, highlighting its role in traditional meals, poetry, and other creative expressions. In Azerbaijan’s Goychay region it is annually celebrated in October/November. Religious people perceive the pomegranate as a symbol of eternity. In 2020 (15.COM) the festival was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[8]

Cultural Identity: The pomegranate’s presence in Alevi culture, from religious rituals to artistic expressions, reinforces its role as a symbol of Alevi identity and heritage.

The Yarsan philosophy is closely related to the Alevi faith and philosophy. It is a belief based on nature, society, nature and social laws and traditions. To show their respect and closeness to nature and society, the Yarsanis, who celebrate all four seasons, celebrate the products they obtained from nature through these feasts. Autumn means Pomegranate Festival for the Yarsanis. Pomegranate is one of the last fruits to ripen. With this festival, the Yarsanis salute the first part of the year while at the same time welcoming the second part.

The Pomegranate Festival, which is celebrated at the end of October every year, starts on Monday and lasts for three days, ending on Wednesday.

Xawenkar: The Pomegranate Festival

The Yarsani Pomegranate Festival, which is also called Ayinê Yari (‘fraternity ceremony’), begins as a religious ceremony. According to the Yarsanis’ belief, Sultan Suhāk [also: Sahak] – the founder of the Yarsan belief – and his friends were trapped in the Mireno cave in Shinawa, Halabja. After three days, the friends broke free and ended up as guests at a poor woman’s house. She only had one rooster, but happily shared it with Sultan Suhāk and his friends. This event took place about 700 years ago. Since then, the Xawenkar feast has been celebrated with roast meat and rice.

The feast of Xawenkar is celebrated as the feast of victory and salvation for Sultan Suhāk and his friends. After the presentation of food and pomegranates, the prayers are read from the book of Yarsan. After the food is eaten and pomegranates offered, the Tambur (drum) groups consisting of hundreds of people begin to play the drum, which is a sacred symbol of Yarsanism. The festival of Xawenkar is celebrated at the grave of Bābā Yādgār, one of the Pirs of the Yarsanis, in Kermanshah Province. Another important shrine is that of Sultan Suhāk in Sheykhan near Perdīvar bridge, also in Kermanshah Province.

Conclusions

This entry describes the significance of the pomegranate as a complex, almost contradictory religious and cultural symbol in the Near East, derived from its meaning as a symbol of fertility, abundance, martyrdom and death. For Alevi communities with a strong natural religious emphasis and affiliation, such as the Ahl-e Haqqi (Yarsan) and Raa Haqi, pomegranates are particularly important for identity forming.

In conclusion, the pomegranate’s association with death is rooted in its cultural, mythological, and historical significance. The fruit’s unique characteristics, such as its seeds and aril, have led to its symbolism in many cultures, particularly in the context of death and the afterlife. Whether it’s seen as a symbol of life, fertility, and abundance or as a fruit of the dead, the pomegranate remains a complex and multifaceted symbol that continues to fascinate and intrigue us to this day.

Aydın, Suphi. 2015. Henarek – Granatäpfelchen: Märchen aus dem Morgenland. Zazaki-Deutsch. Hamburg: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung.

Israelmagazin. 2011. “How Many Seeds Does a Pomegranate Actually Have? The Myth of the Perfect Number.” Israelmagazin, 12 October 2011. https://www.israelmagazin.de/wie-viele-kerne-hat-ein-granatapfel.

Killy, Daniel. 2023. “Pomegranate: The Most Jewish Fruit.” Jüdische Allgemeine, 15 September 2023. https://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/kultur/die-juedischste-frucht/.

Lechner-Masser, Susanne. 2017. Biblische Gestalten im jüdischen Religionsunterricht [Biblical Figures in Jewish Religious Education]. Lübeck: Schöningh.

UNESCO. n.d. “Nar Bayrami: Traditional Pomegranate Festivity and Culture.” Intangible Cultural Heritage. https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/nar-bayrami-traditional-pomegranate-festivity-and-culture-01511.

Zekert, Otto, ed. 1938. Dispensatorium pro pharmacopoeis Viennensibus in Austria 1570. Published by the Austrian Pharmacists’ Association and the Society for the History of Pharmacy. Berlin: Deutscher Apotheker-Verlag Hans Hösel.