A Brief History of Bağlama

* This entry was originally written in Turkish.

The bağlama is, as in the past, still the most important instrument of our folk music today. It would not be inaccurate to say that one of the principal factors behind the bağlama’s increasing diffusion is the significant impact of developing technology. Thanks to the spread of media such as radio, television and especially the internet, the bağlama occupies a more popular place in its own history than ever before. People living abroad, who are outside the culture but devoted to the music, are today learning the bağlama and conducting various scholarly studies such as articles and theses about it. The bağlama, thought to have evolved from the kopuz, has over time spread to different geographies, contributing to the enrichment of the cultures of the societies in which it is found. This study presents information on the brief history, etymology, development, structural features, types and geographical diffusion of the bağlama.*Figures and visuals are included in the gallery.

The Etymology and History of the Kopuz

It has been established that the name kopuz appears in the Yenisei monuments. In many dialects and accents used by the Turks, this name has reached the present day in forms that have hardly changed at all, such as kobuz, kobus, kobız, kobıs, komız, komıs, küpüz, kupüz, komuz, komus, homus, kubıç and qobuz (Eroğlu, 2011: 7). The studies of Gâzimhâl and Kemal Eraslan state that the name kopuz may have derived from the word kop (cited in Parlak, 1998: 18).

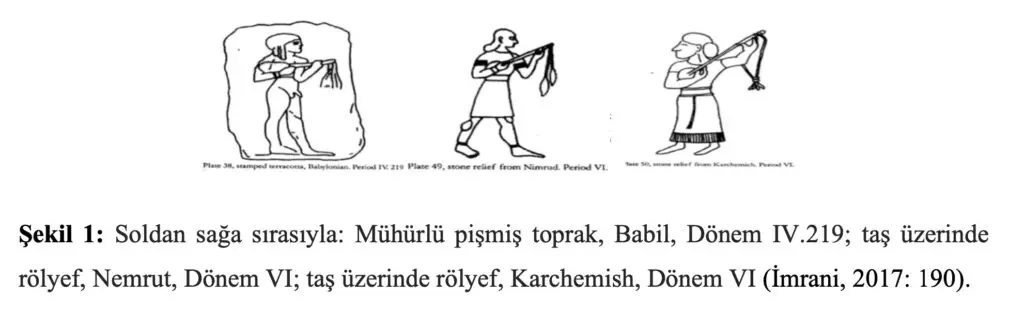

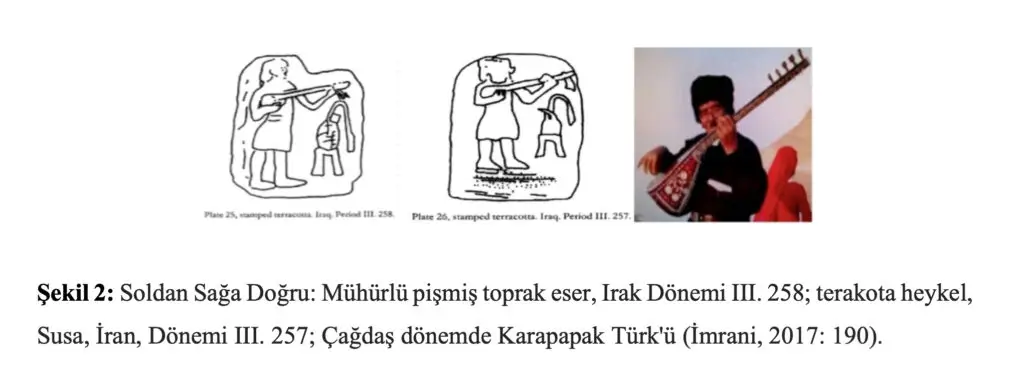

Stone reliefs and carvings unearthed in archaeological excavations in Anatolia have provided important clues about instruments that closely resemble the bağlama. In these reliefs belonging to the Greek, Hittite and Sumerian civilisations, instruments very similar to the bağlama have been encountered. Furthermore, the first written sources concerning the bağlama are found in Chinese archives dating to the first century CE (Koç, 2000: 5).

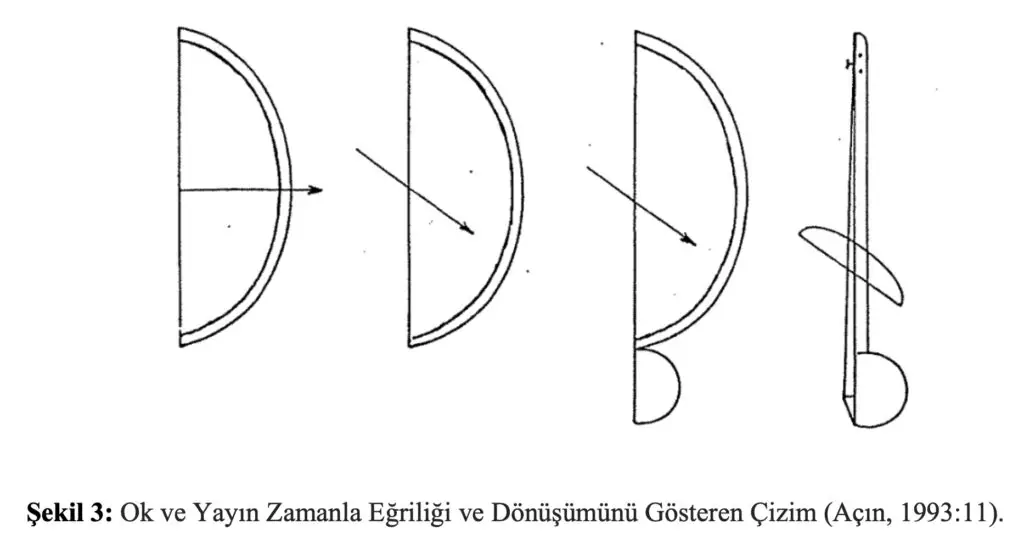

The most significant details shown in Figures 1 and 2, played in a way quite similar to the bağlama, are instruments that are derivatives of the kopuz such as the tar and, in Azerbaijan, the instrument known as the aşık sazı, which is played slung over the shoulder. When evaluated in terms of performance, the bağlama is played on the lap. Whether the instruments in these drawings are in fact bağlamas remains a matter of debate (İmrani, 2017: 189). Various theories exist that the kopuz may have derived from the bow and arrow. According to Ögel, the kopuz was initially played by hand, and later began to be played with a bow; these two tools influenced the development of the kopuz (Parlak, 1998: 18). Similarly, Gazimihal stated that the ıklığ kopuz appeared after the bowless kopuz (Gazimihal, 1975: 14). The drawing in Figure 3 shows, according to Açın, how instruments such as the okluğ and ıklığ, obtained from the bow and arrow, evolved. With this transformation, it is thought that the kopuz family developed and diversified in line with the needs of societies.

Traditional playing techniques on the kopuz are divided into two: şelpe (playing by hand) and playing with a bow. The şelpe technique is used on the stringed types of kopuz and is based on striking and plucking the strings with the right hand through upward and downward movements towards the soundboard and the top. The bowed types of kopuz are performed with techniques that prioritise the use of the bow. However, on the kopuz the şelpe technique is applied far more commonly than bowing (G. Kızıler, 2007: 31). Mahmut Râgıp Gâzimihâl (1975: 67), who produced important studies on Turkish music and instruments and made valuable contributions to the field, notes that the kopuz spread over a wide geography among Turkish communities in the 12th and 13th centuries CE. With this spread, a musical class called “kopuzcu” emerged. He also states that the inscription “kopuzcu” is encountered on tombstones, giving as an example the grave of Mengutaş Tay, who died in 1212 CE.

Structural Features of the Kopuz

Today, the kopuz instrument is used in Anatolia and Central Asia. Although the playing characteristics of the earliest kopuz are not known precisely, in terms of physical details, it is known that its strings were made of horsehair or gut and that it was played with the fingers. There are models without a soundboard for acoustic resonance as well as models with soundboards made of skin and wood. The use of skin and wood for the soundboard is thought to have developed in later periods. The use of metal strings on the kopuz and the start of playing with a plectrum (tezene) reveal one of the important performance differences between the earliest kopuz and the modern bağlama (Parlak, 2000: 1). On the other hand, there is also the mouth kopuz, which is played with the mouth, classified among the struck-wind instruments, and produces impressive sounds by imitating animal and natural sounds. Today, mouth kopuzes made of metal are found among the Turks of Central Asia and in northern Mongolia, while models made of bamboo are found in India and the oceanic islands. Researchers suggest that the mouth kopuz has a history of approximately 6,000 years (Yeşil, 2015: 194).

Types of Kopuz

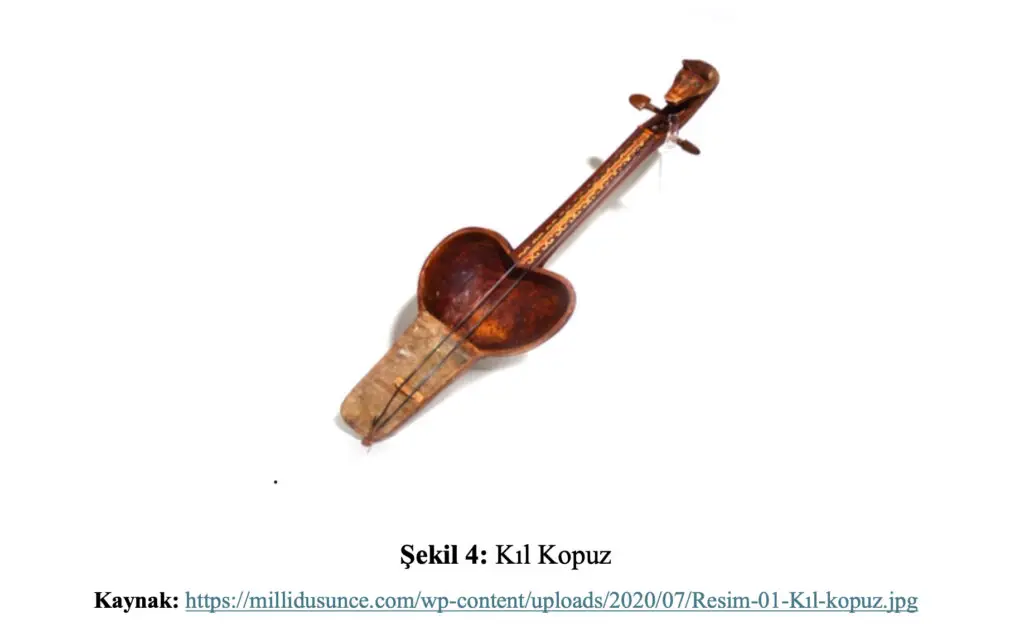

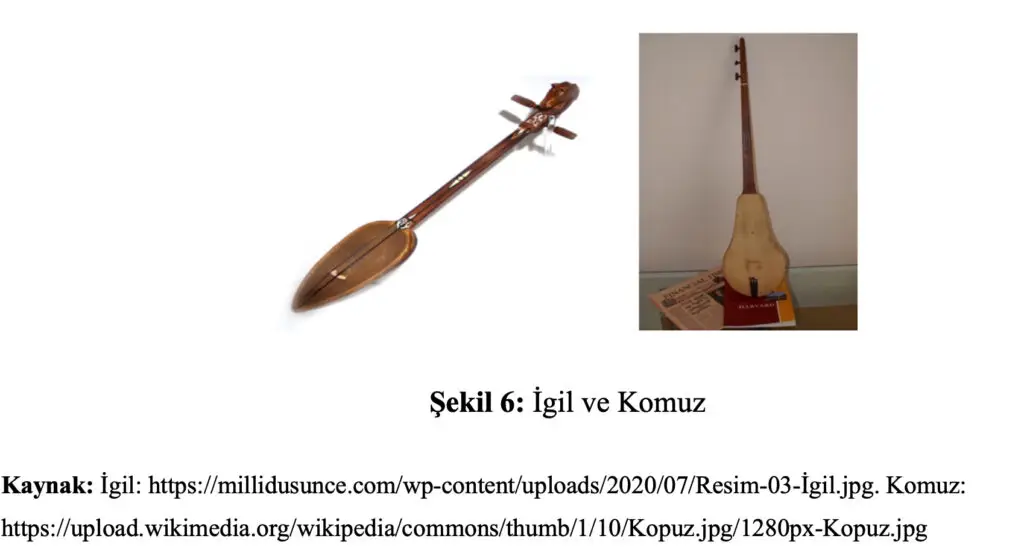

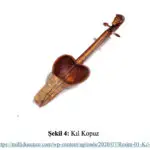

With the wide geographical spread of the kopuz instrument, it may be said that its different variations multiplied over time. It is more accurate to classify all the instruments derived from the kopuz as “types of kopuz”. Among these types are instruments such as komuz, okça komız, çertme, çartı kopuz, şerçeng komıs, şertpe komus, kıl kopuz, kaylaçang kobız, buçı kopuz, ağaç komus, yadıngı komus, temir kopuz, kat komus, topşugur, dutar, setar, saz, tanbur, dombra, şerter, çağur (çöğür) and yelteleme (Parlak, 1998: 26-41). Traditionally the kopuz is played by hand (without a plectrum) and with a bow. In the hand-playing technique, sound is produced by striking or plucking the strings from above and below with the right hand. This technique is applied mostly on the strings close to the body of the instrument. In the bowed kopuz family, the playing is performed using a bow. However, in general use, playing the kopuz by hand is more common than bowing (G. Kızıler, 2007: 31). A type that is still performed today and is regarded as the earliest example of the kopuz is the “kıl kopuz“, described in Figure 4. The bowed and plucked instruments derived from the kıl kopuz spread to different geographies over time. This instrument can be played with the fingers or the nails. Other Turkish instruments played with the nail include the igil and the classical kemençe. While the classical kemençe is played only with the nail, the kıl kopuz and igil can be played both with the nail and with the fingers. There are also various views that the name of the igil instrument transformed from “ikiliden” (from ‘twofold’) to “ikitelli saz” (‘two-stringed instrument’) due to its double-stringed structure.

The hegit instrument shown in Figure 5 is an instrument that was brought to Anatolia and has survived to the present day, having evolved over time from the name ıklığ (Akyol, 2017: 164). The hegit, which has today almost fallen into oblivion, is generally made from a gourd and is played with two strings. In addition, there are examples produced from wood. This instrument is thought to have had an important role in the transition from the bowed kopuz to the plucked kopuz.

Today in Anatolia, the two-stringed ıklığ-now rapidly diminishing and nearly forgotten-still has, to some extent, a field of use. The ıklığ instrument shown in Visual 1, which has a direct counterpart in Asia and has largely preserved its original form in Anatolia, over time changed shape with the emergence of three-stringed versions and evolved into another musical instrument. The continued existence and preservation of the earliest versions of the ıklığ in Anatolia today shows how strongly the people of Anatolia have maintained their connection with their past (Akyol, 2017: 167).

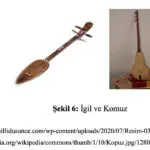

An important stage in the transition from the kıl kopuz-that is, a bowed instrument-to a plucked instrument is the komuz played by the Kyrgyz Turks, seen on the right in Figure 6. Among the plucked instruments belonging to the kopuz family, the komuz is the only instrument without frets. This feature positions the komuz as a stage in the transition from the bowed instrument kıl kopuz or from the igil instrument, shown on the left in Figure 6, to a plucked instrument. After this transitional phase, the hand-played instruments of the kopuz family began to develop.

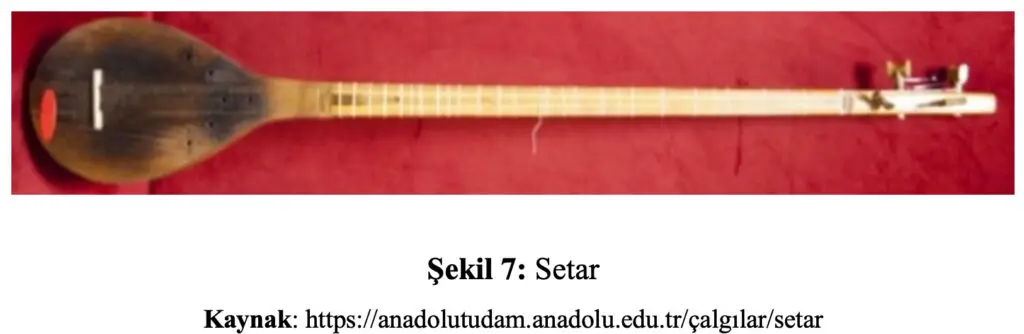

The saz seen in Figure 7, which comes from the kopuz family, is the setar used in Iran. The setar is an instrument consisting of three strings and four pegs; its body resembles the Iranian tanbur, but it has a longer neck. It shows greater similarity to the dutar of Uzbekistan and the Uyghurs. Today it is frequently preferred in Iran at weddings, community events and various organisations (Kafkasyalı, 2018: 828).

Figure 8 shows the tanbur used in Iran, which has a structure similar to that of the dede sazı in Anatolia. This instrument, generally played by the Ahl-i Haqq community living in Iran, has two strings. The Ahl-i Haqq, who can be considered an extension of Alevi culture in Iran, form an important religious bond through the tanbur (Özdemir, 2009: 23).

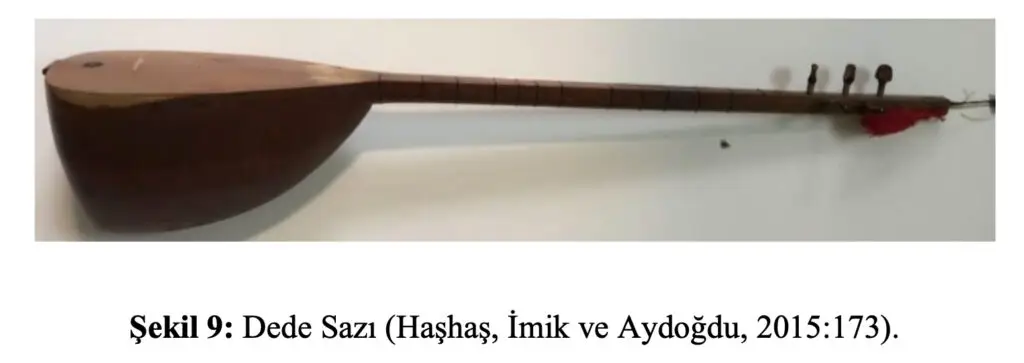

A type of bağlama used in Alevi-Bektashi cem rituals and conversations is the dede sazı shown in Figure 9. Although the dede sazı shows small differences according to region, it generally has a structure with 12 frets and 3 strings. Although the bowl size and the number of strings vary from region to region, in some regions the saz is used with 2 strings and in others with 3 strings. The bowl form is known as the “axe bowl” (balta tekne) and this is its most distinctive feature. Today it is used intensively by Alevi Dedes and Zâkirs especially in regions such as Malatya, Tunceli, Sivas, Tokat, Adıyaman and Kahramanmaraş (Haşhaş, İmik and Aydoğdu, 2015: 171).

The Geography of the Kopuz’s Spread

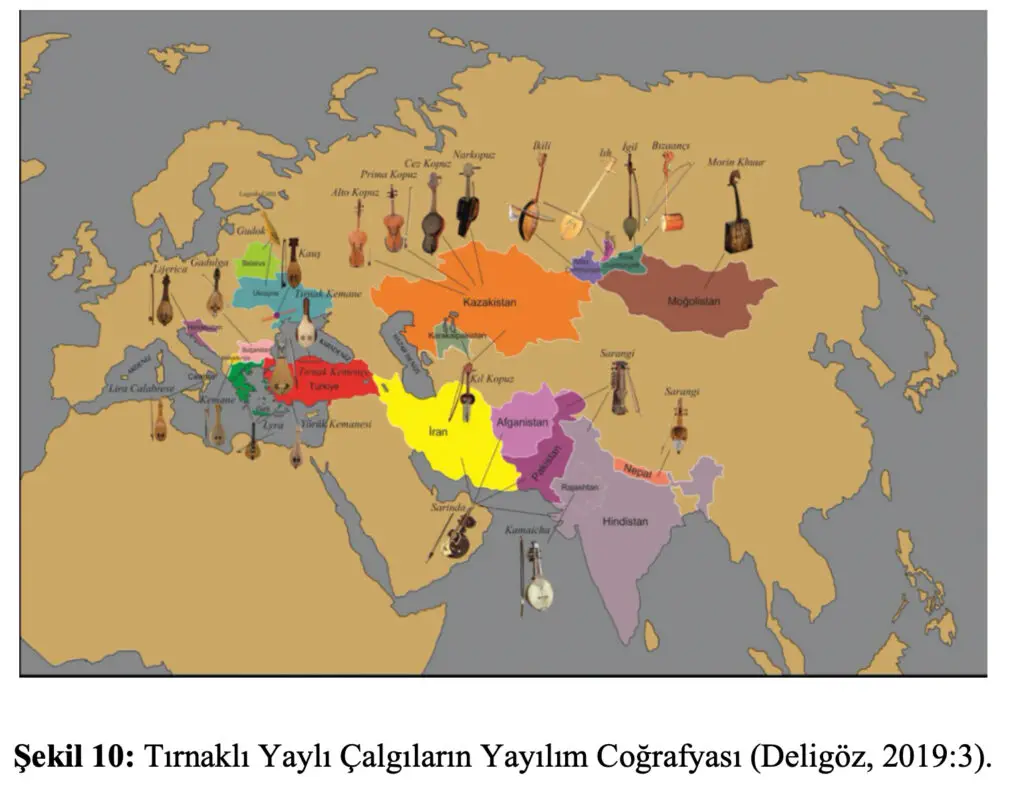

It is understood that the kopuz was first derived from the bow and arrow and divided into bowed and plucked instruments, and that various changes occurred in the structure of the instrument during this process. Although it is known that the Turks led a nomadic life before settling, it is seen that their interactions with other peoples expanded the spread of the kopuz instrument. Considering that bowed instruments became widespread in different geographies worldwide, it may be concluded that cultural differences contributed to the diversification of these instruments among societies. It has been noted that bowed instruments played with fingers and nails also laid the groundwork for the development of plucked instruments over time (Deligöz, 2019: 2). In particular, the kıl kopuz and the igil among bowed instruments are thought to have had an important role in the transition to plucked instruments. In Figure 10 the areas of bowed instruments played with the nail is observed; it is stated that a similar geographical distribution applies to plucked instruments. It is proposed that the kopuz transformed into instruments such as the dutar, dombra, komuz and setar in Asia; the bağlama in Anatolia; the ud and lavta in the Middle East; and the guitar and the violin family in Europe.

The Journey of the Kopuz Instrument’s Arrival in Anatolia

Kopuz is a generic name given to the instruments of the Turks. All instruments played with the mouth, bow, nail and plectrum are given this name (Yeşil, 2015: 193). The discovery of bağlama-like instruments in archaeological excavations in Anatolia, Iran and Azerbaijan; the detailed description of the kopuz in Chinese sources; and the unearthing of old kopuz examples in excavations in Central Asia have prevented definitive conclusions as to the geography in which these instruments were first used. Some researchers seek the origin of the bağlama in Anatolia, while another group argues that its roots lie in Central Asia. On the other hand, in Central Asia today, it is very common to encounter the kopuz and its derivatives being played by hand. In these instruments used in the Turkic republics, the hand technique is highly developed. In Anatolia, however, the tradition of hand-playing has almost been forgotten over time due to the transition to plectrum use. Although historically the bağlama is an instrument played by hand, the plectrum has also made important contributions to the bağlama’s development. Technically, progress and the diversification of styles and manners accelerated further with the use of the plectrum.

Structural Changes that Formed Over Time in the Kopuz Instrument

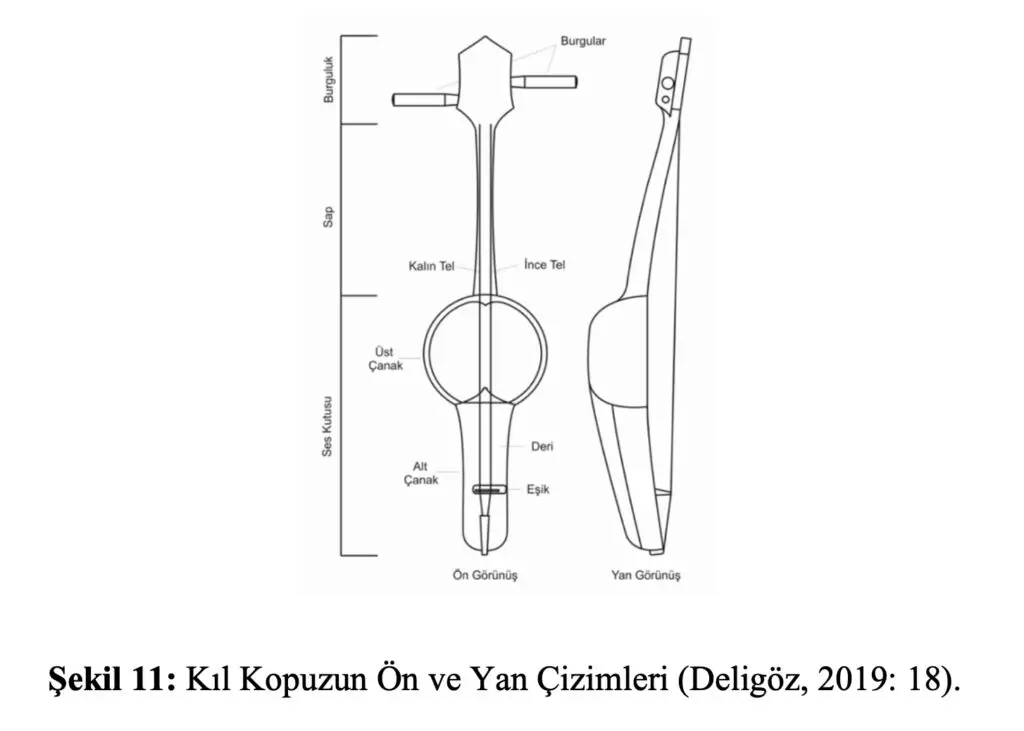

The exterior of the kıl kopuz, seen in Visual 2, is pear-shaped and its fingerboard is fretless. In the earliest examples of the kopuz there is no soundboard. In later periods the use of skin on the soundboard became widespread. In the pear-shaped bowl section, horsehair strings were preferred initially, and in later periods gut strings were adopted.

Looking at the drawing of the kıl kopuz in Figure 11, it is seen to have a structure that resembles a ladle at the front and a bow on the side. This instrument, which has no fixed standards, has a length varying between 60 and 76 cm and a width between 13 and 21 cm (Deligöz, 2019: 17). Gazimihal (1975: 43) notes that in the Dede Korkut stories the kopuz is sometimes called “elce kopuz” instead of “kolca“. He also states that the expression “kolca” is used to refer to the situation where the left hand is opened towards the fingerboard.

The fingerboard and the bowl of the kopuz were initially designed as a single piece, whereas in later periods it was observed that the fingerboard and the bowl were produced separately and then joined. With this innovation, holes began to be used in the bowl and the soundboard. During the process of the kopuz’s transformation from a bowed to a plucked instrument, the replacement of skin with wood as the soundboard material enabled the instrument to diversify. While there were no frets on the fingerboard in the earliest examples, over time fret applications appeared on the fingerboard. The first frets used were made of horsehair; in later periods gut frets and metal frets (especially copper) were preferred (Gazimihal, 1975: 24).

These structural changes to the kopuz were realised through the people’s own contributions. Products belonging to folk culture are generally unassuming; they are regarded as ordinary parts of everyday life. The changes made to the kopuz were likewise conceived purely as a means to make music and did not seek to lay claim to anything (Demir, 2020: 163).

The Transformation of the Name Kopuz into Bağlama

In Anatolia, changes occurred in the structure of the kopuz over time. In this process, metal strings began to be used instead of gut strings; hand-playing gave way to the use of a plectrum; and wooden materials were preferred for the soundboard instead of skin. With these changes, the kopuz acquired a different character. The inclusion in Gökhan Ekim’s 2002 master’s thesis on the historical development of the bağlama of the remarks of Evliya Çelebi constitutes a good example of this transformation. Evliya Çelebi stated, by saying “I have not seen its like in Anatolia”, that the kopuz had undergone physical changes.

The name kopuz also found a place in the poems of such important figures of our literature as Yunus Emre and Kaygusuz Abdal. For example, in one of Yunus Emre’s poems, both the kopuz and the saz are mentioned.

The fact that the name kopuz is not encountered in Anatolia after the 17th century does not mean that this instrument disappeared entirely; it simply shows that it assumed a different form through certain physical changes. Foremost among these changes are the preference for wood rather than skin for the soundboard, the tying of frets on the fingerboard, the transition of the bowl structure to a more angular form, and the use of metal strings instead of gut strings. All these factors resulted in the kopuz taking the name bağlama.

After the kopuz, the name first used for this instrument was “saz“. Although the word saz is of Persian origin and does not conform to the morphological structure of Turkish, it is suggested that over time it acquired a different meaning in Turkish through its association with the word sızı (‘ache’). This expression, evoking the ache in the heart of the minstrels and the sighing sound made by reed-beds, was adopted over time as the new name that replaced the kopuz. A second name later used for the “kopuz” instrument was “bağlama”. It is stated that the name bağlama derives from the tying of frets on the neck of the instrument (Parlak, 1998: 55).

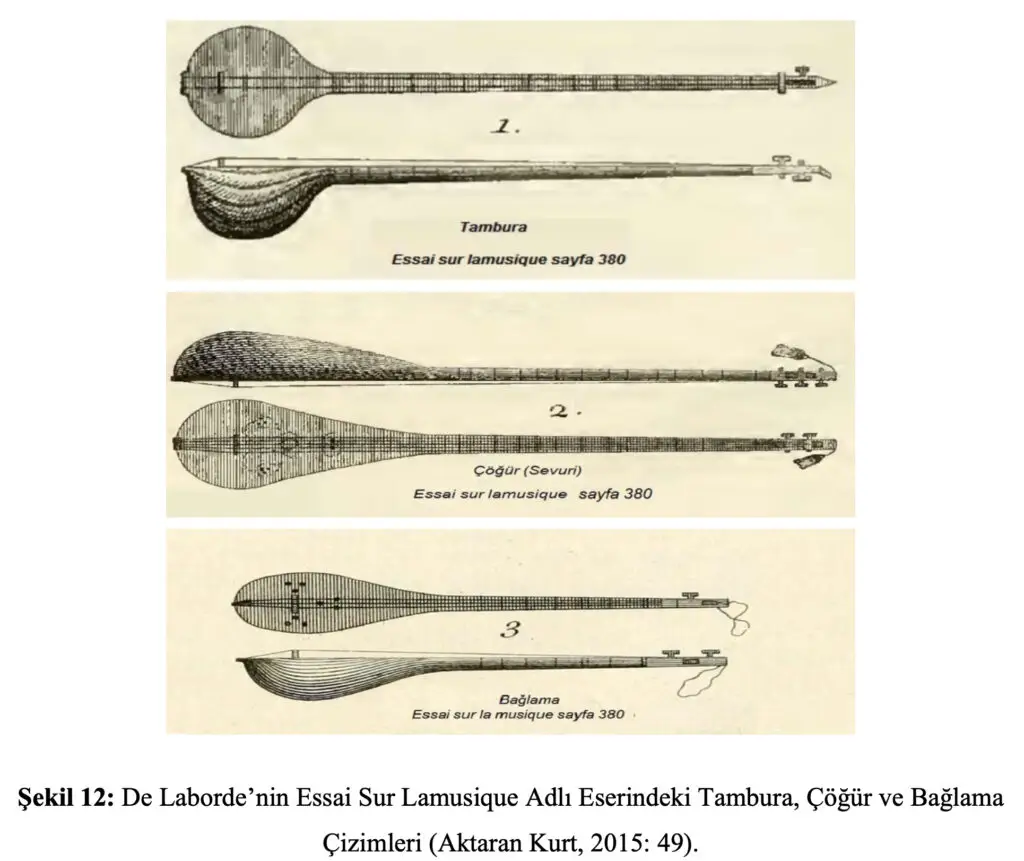

According to written sources, the first person to use the term bağlama was the French writer De Laborde. De Laborde mentioned the bağlama in his work “Essai sur la musique”, published in Paris in 1780. This work was prepared in detail and included drawings of instruments (cited in Kurt, 2015: 48). Among the drawings in the book are images of the tambura, the çöğür and the bağlama.

As can be understood from the drawings, the tambura has a neck that is quite long compared to its bowl. Owing to the number of frets being close to 19, this shows great similarity to the dutar used among the Uighur and Uzbek Turks. Looking at the çöğür, it attracts attention with a larger bowl structure resembling a pear-shaped body and with 15 frets. On the other hand, it is seen that the bağlama has quite a short neck; and the bowl and neck are almost equal in length.

In bağlamas made today with 19 frets, it is likewise observed that the lengths of the bowl and the neck are equal. In light of this information, it appears possible to say that the bağlama has reached the present day without undergoing a significant change. However, it should be noted that there is diversity only in the number of frets, and this is still observed today (Kurt, 2015: 50).

The Process of Hand-Playing on the Bağlama and the Transition to the Plectrum

It is seen that the hand-playing technique was used first on the bağlama. Over time, this technique developed and progressed. Especially in the musical performances of the Turks of Central Asia, the hand-playing technique held an important place. In the geography of Central Asia, hand-playing techniques display more variety than in Anatolia. However, because the bağlama’s volume is lower than that of other bowed and wind instruments, solutions were sought. With the replacement of gut with metal strings, the playing of the bağlama became harder, and accordingly an increase in sound level was recorded. This hardness led to the use of early examples of the plectrum; materials such as eagle wing and bone were preferred. In the subsequent period, with the use of cherry bark and the thin parts of bone instead of these materials, it is understood that the plectrum reached a more developed form. In time the plectrum acquired a structure resembling today’s dimensions and style.

It is thought that the plectrum began to be used on the bağlama in the 17th century and that this use became fully established in the 18th century. The researcher Gazimihal stated that De Laborde’s text is the oldest known written description of the bağlama. De Laborde described the bağlama or tanbur in similar physical terms; he stated that two of its three metal strings were steel and one was brass. He also reported that feathers were used so that the sounds would be sharper and louder. This information shows that, in the early period, the plectrum on the bağlama was made of feather or wing parts. Over time this technique gained social acceptance and became traditional. Thus, the use of the hand-playing technique decreased, and the plectrum method came to be adopted in the main.

The bağlama developed a performance style of its own in Anatolia; especially the use of the plectrum soon integrated with styles and techniques that varied by region. While playing the bağlama with the plectrum became increasingly widespread, the hand-playing technique continued primarily within Alevi-Bektashi musical culture and in regions such as the Teke region. However, the increasing preference for the plectrum brought hand-playing to the point of near oblivion. Owing to the impact of urbanisation, many people abandoned the method of hand-playing and turned to the use of the plectrum; as a result, the hand-playing technique came to be performed by a small community in rural areas.

Among the prominent bağlama masters of the period, Aşık Davut Sulari, Aşık Daimî, Ali Ekber Çiçek and Aşık Mahzuni Şerif initially used the şelpe (hand-playing) method but later transitioned to playing with a plectrum. However, there were also masters who did not abandon the hand-playing technique; masters such as Nesimi Çimen and Ramazan Güngör continued this method. In later years, Hasret Gültekin’s interest in hand-playing, and Arif Sağ’s performance of the pieces “Gurbet Havası” and “Teke Zortlatması” with the şelpe method at his 1986 Gülhane Concert, drew renewed attention to this technique. In addition, the Resistance Concert organised by Arif Sağ in 1993 and the release of the album bearing the same name enabled the hand-playing technique to regain importance (Mert, 2018: 72).

The Formation of Styles and Manners on the Bağlama

The use of the plectrum on the bağlama enabled the emergence of various playing techniques. Techniques performed with the plectrum such as sweeping (tarama), striking (çarpma) and sliding (sıyırtma) provided the ground for the shaping of plectrum styles. In particular, certain tunings facilitated the use of the plectrum and led to the development of styles within those tunings. In this context, the bozuk düzen (tuning) generally comes to the fore among the tunings that are effective in shaping styles. Today almost all styles in use are performed in bozuk tuning. Gazimihal (1975: 146) emphasised that the performance of bozuk tuning is considered difficult by saz players. This difficulty stems from the requirement to strike the top string rapidly and staccato with the plectrum while striking the lower and upper strings within the same duration. At this point Gazimihal also provides important clues as to how styles were formed.

The difficulty of performance directed players who wished to master the bağlama towards the bozuk düzen, and this led to the spread of the tuning and contributed to the formation of a diversity of styles. Moreover, Gazimihal stated that bağlama tuning found a wider field of use; the chief reason for this is that the performance of bağlama tuning is easier. Additionally, the fact that plectrum techniques were performed in different ways in certain regions led to the emergence of region-specific plectrum styles. Regional plectrum techniques such as the Kayseri style, Yozgat style and Konya style subsequently spread to other regions, laying the groundwork for the formation of new plectrum techniques.

Bağlama performers developed various plectrum techniques in order to demonstrate their mastery of the plectrum (Koç, 2000: 14). Parlak (2000: 68) notes that the earliest culture of plectrum performance on the bağlama was inspired by Tanburi Mesut Cemil, including by Muzaffer Sarısözen and the bağlama artists of Yurttan Sesler. Parlak also states that the striking forms performed by hand prior to the plectrum-such as tarama, çırpma and ezme-produced distinctive melodic varieties with the transition to the plectrum, and that this gave the plectrum strokes a regional character, enabling the emergence of new styles.

At first, plectrum performances were executed by striking all the strings; this stemmed from a habit brought by the şelpe technique. Later, masters such as Bayram Aracı, Tanburacı Osman Pehlivan and Zekeriya Bozdağ gave melodies an aesthetic form by using different plectrum techniques on the bağlama and ensured their adoption. Arif Sağ, on the other hand, replaced the understanding of striking all the strings with the plectrum with an understanding of playing the melody on the strings individually (Parlak, 2000: 71).

Types of Bağlama

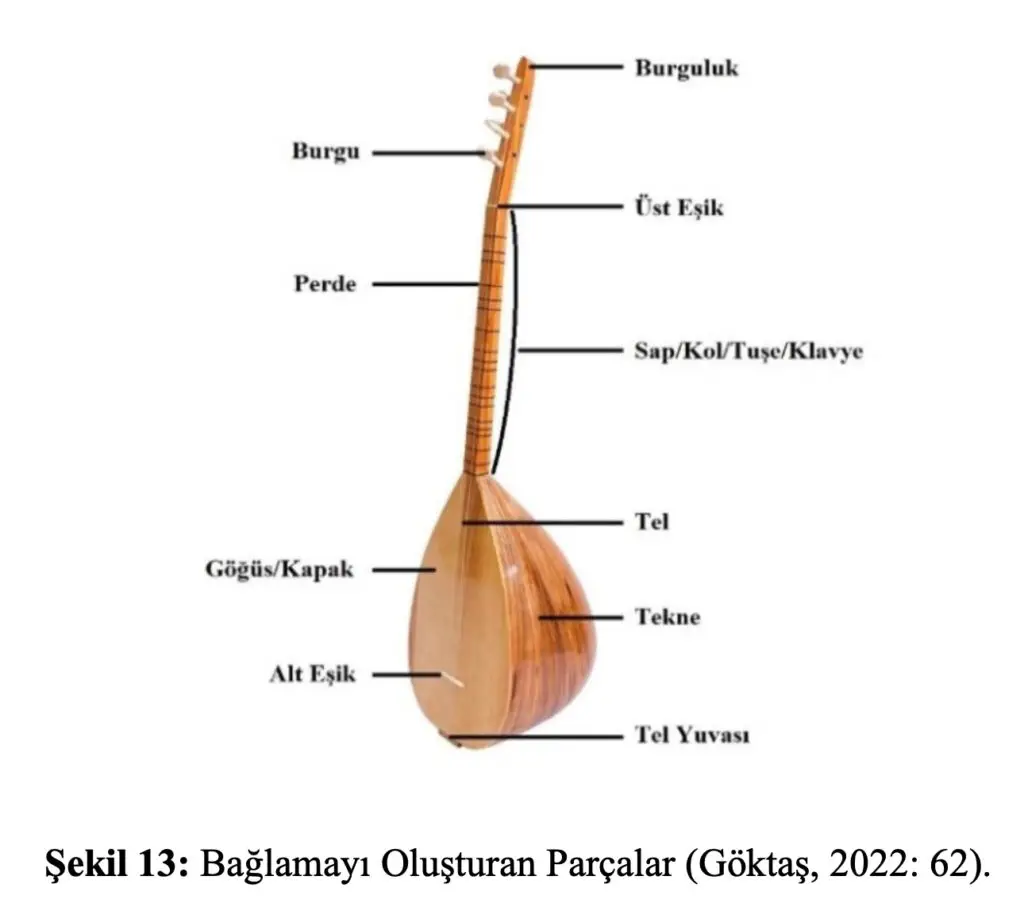

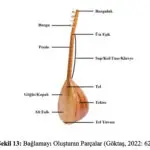

The bağlama stands out as a highly rich instrument in terms of tuning, structure and style. The structure of the bağlama shown in Figure 13 contains in its 17-fret system the arrangement created by Safiyüddin Urmevi and Abdulkadir Meragi. With these features it is the most widely used instrument of the family. However, terms such as “short-neck” and “long-neck” are misleading. It is considered a more accurate approach to define the bağlama according to the number of frets (Ekim, 2002: 31-38). Similarly, Okan Murat Öztürk (2007: 14) also states that the sound system created by Farabi and Safiyüddin exists in different varieties of the bağlama family with an octave arrangement (with 10, 12, 14, 18 or 20 frets).

When the bağlama family is ordered from the largest size to the smallest, the meydan bağlaması, shown in Figure 14, as its name suggests, is the largest of the bağlamas played in the meydan (assembly). The length of its bowl starts from 52 cm.

The Divan Bağlama is the second largest instrument, notable for its size. It is generally produced with 7 or 9 strings. Instruments whose bowl size varies between 45 and 50 centimetres fall into this category. The divan saz shown in Figure 15 is given as a fine example of this type (Çiçekçioğlu, 2017, 4-5).

The baz is an instrument used by the Yörük Turkmens of southern Anatolia and is generally played with 5 or 7 strings. The çöğür has a round bowl form similar to the structure of the tanbur instrument, as well as a drop-shaped form. Initially the çöğür bağlama had a bowl size the same as the divan bağlama, but over time it acquired a smaller bowl design. The çöğür bağlama shown in Figure 16 is presented as an example with a large bowl form. This instrument can be played with 6 or 9 strings and has a total of 15 frets (Çiçekçioğlu, 2017, pp. 4-5). The number of frets indicated for the çöğür bağlama in the figure was increased in order to meet the need for notes.

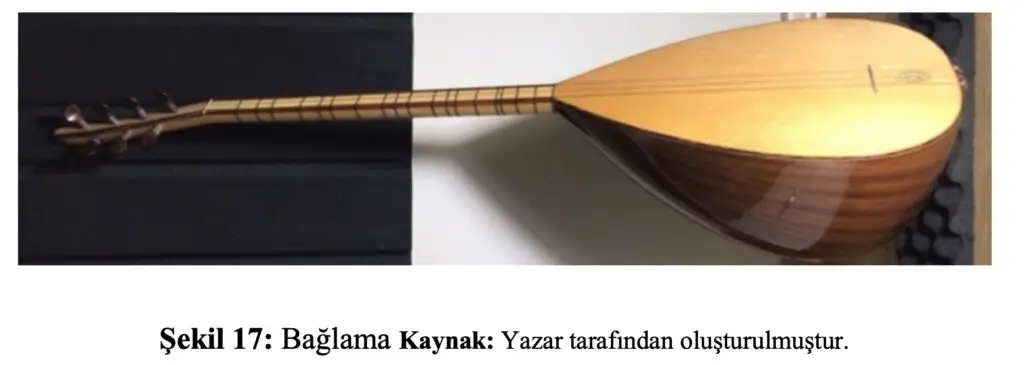

The bağlama, the instrument that gives its name to the family, is performed with 6 or 9 strings and has 17 or 24 frets. The bağlama shown in Figure 17 has bowl and neck lengths of 40 cm. It stands out as the most commonly used instrument within the family (Çiçekçioğlu, 2017, pp. 4-5).

The bozuk has a very widespread field of use in Anatolia. It generally has 15 or 18 frets and consists of a total of 9 strings. The Aşık bağlama shown in Figure 18 is among the instruments most preferred by Aşıks and Ozans. This instrument differs from the others in that its neck is somewhat shorter. It consists of 13 or 15 frets and is performed with 6 or 9 strings (Çiçekçioğlu, 2017, pp. 4-5).

The tanbura bağlama shown in Figure 19 appears to be a reduced version of the large-bowled divan bağlama. It is generally preferred with 6 strings (Çiçekçioğlu, 2017, 4-5).

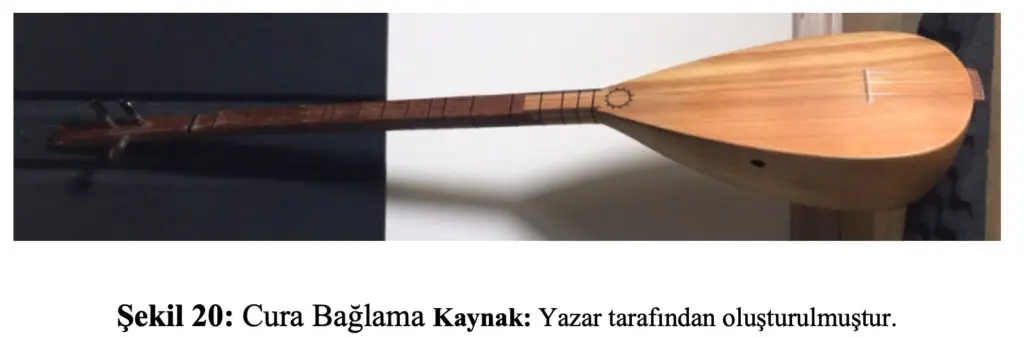

The cura bağlama, as in the example shown in Figure 20, is an instrument widely preferred in performances of Turkish folk music. It attracts attention with its high-frequency sound character and, thanks to this feature, has become an important component of bağlama orchestras. The cura bağlama, which may be considered a smaller version of the bağlama, generally has 3 or 6 strings.

The two-stringed instrument is one of the oldest instruments of the bağlama family and has similar versions in Central Asia in terms of both structure and playing technique. This instrument is similar in size to the cura bağlama and has two strings. On the other hand, the bulgari takes its name from the Bulgar Türk tribe and may have two or four strings, with a total of 16 frets. The kara düzen instrument is a widely used hand-played instrument in the Adana-Gaziantep regions, known as the Barak region. The ırızva is an instrument used in the south of Anatolia; it has four pegs but three strings, and 13 frets.

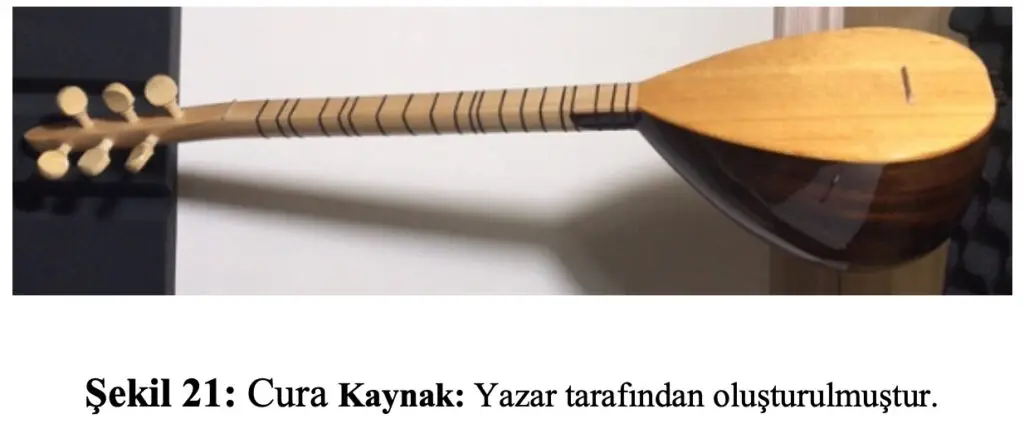

The cura shown in Figure 21 is among the smallest-sized instruments of the bağlama family. It generally has 7 or 16 frets and is mostly performed in 3- or 6-string examples. Various tunings belonging to the bağlama family are used on the cura instrument. In particular, since it is played with the fingers in the Teke region, it is known locally as the parmak curası (Çiçekçioğlu, 2017, 4-5).

Conclusion

The journey the kopuz has undertaken throughout history has enabled it to be called by different names through various transformations across different cultures and geographies, and has bequeathed to Anatolia a broad diversity that extends from its roots to the bağlama family. Looking at the past of the kopuz, it is possible to see its traces in many places, from Anatolia to Chinese civilisation. There is evidence for the use of kopuz-like instruments in many regions such as Asia, Anatolia and the Balkans. Today, debates continue as to precisely where in the world the kopuz spread from. The discussion as to whether it was Central Asia or Anatolia reveals its historical significance. Considering its presence in Anatolia, the inscriptions on the tombstones of minstrels buried with the kopuz emphasise this instrument’s cultural and spiritual value. Over time, the kopuz underwent structural changes and took the name bağlama in Anatolia. Behind this transformation of the bağlama- the fundamental instrument of Turkish folk music-lies the significant role of human agency. In this section of our study, we address the factors that influenced the evolution of the bağlama through conclusions and recommendations. Although there is no definitive information about the birthplace of the kopuz, certain ideas have been put forward. This instrument spread through different cultures, undergoing changes in line with human needs and demands. The depiction of kopuz-like instruments in the reliefs found in Anatolia among the Hittites and in the east in Iran and Azerbaijan reveals its historical significance. Instruments likewise had a distinct place in people’s lives in the past and left strong effects in the cultural layers of societies. In addition, it is seen that the kopuz is mentioned in Chinese sources, which shows that it was known across a wide geography. The presence of the kopuz in the poems of minstrels such as Yunus Emre and Kaygusuz Abdal, and Mevlana’s use of the kopuz in lovers’ conversations, shows that even the religious figures of the period forged a bond with music and instruments. Over time, the word kopuz transformed in meaning and took the name bağlama. Although researchers have not yet reached a definitive conclusion on the transformation from kopuz to bağlama, various views have been put forward regarding the structural changes of the instrument: the addition of frets to the fretless structure; the use of wood rather than skin on the soundboard; the replacement of gut strings with steel strings; and the addition of the plectrum to the şelpe performance are among these factors. It is particularly noted that the addition of frets has been widely accepted. It is known that the bağlama was played with şelpe in its earliest periods and that gut strings were widely used. However, because this type of string produced a low volume, the instrument’s acoustic audibility remained weak. It is thought that the first use of metal strings began from the 14th century. Steel strings increased the volume of the bağlama and raised its timbre. This increased sonic intensity with steel strings paved the way for the bağlama’s encounter with the plectrum. The earliest examples of the plectrum, made from bird feather, bone and cherry bark, added a richness of style to the bağlama. However, it was noticed that the acoustic holes used on the soundboard had negative effects on plectrum performance, and over time their use was abandoned. Significant changes were also observed in the bowl structure of the instrument; from the sharp lines known as the axe bowl (balta tekne), a more rounded form was adopted, and different systems were applied at the string attachment points. Although minor differences exist today, it is noteworthy that the general form of the bağlama has been preserved. The continuing use of the balta tekne and the older string systems in the dede sazı performed with şelpe is still prevalent particularly among Alevi-Bektashi and Yörük communities.

Açın, Selçuk Yavuz. 1993. Türk Halk Müziği Yaylı Sazlarından Kemanenin Doğuşu, Yapımı ve Ailesinin Oluşması. Yüksek lisans tezi, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Akyol, Ali. 2017. “Kabak Kemanenin Dünü, Bugünü ve Yarını.” İnönü Üniversitesi Kültür ve Sanat Dergisi 3 (1): 163-181.

Çiçekçioğlu, Ümit. 2017. Bağlama Yapımında Yenilikçi Yaklaşımlar. Yüksek lisans tezi, Ege Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Deligöz, Ali. 2019. Hakasya, Tuva, Altay, Kazakistan ve Türkiye’de 18. Yüzyıldan Günümüze Tırnak Yaylı Çalgılar. Doktora tezi, Ege Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Demir, Ali, ve Cengiz Demir. 2023. Kısa Sap Bağlama Metodu ve Türkü Repertuarı. Ankara: Eos Yayınevi.

Gâzimihâl, Mahmut Ragıp. 1975. Ülkelerde Kopuz ve Tezeneli Sazlarımız. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları.

Göktaş, Uğur. 2022. “Bağlamadaki Mevcut Öğrenme Yollarına Yönelik Çeşitli Tespitler.” Atlas Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 1 (11): 61-90.

Gülay Kızıler, Zeynep. 2007. Bağlamadaki Şelpe Tekniği Yeni Uygulamalarının Armonik ve Melodik Yönden Analizi. Yüksek lisans tezi, Başkent Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Haşhaş, Serkan, Ümit İmik ve Cem Aydoğdu. 2015. “Arguvan Örnekleminde ‘Dede Sazı’nın Organolojisi ve İcra Özellikleri.” Cumhuriyet Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 39 (1): 169-180.

İmrani, Ramazan. 2017. “Arkeoloji Kazıntılarda Karapapak Türklerinin Saz ve Âşıklık Geleneği Tarihi.” International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Intercultural Art 2 (2): 183-207.

Kafkasyalı, Yusuf Selman. 2018. “İran’da Türk Millî Kimliğinin Sürdürülmesinde Müziğin İşlevi.” Turkish Studies 13 (18): 821-831. https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.13822

Koç, Ali. 2000. Bağlama Eğitiminde Görülen Problemler ve Bunların Çözüm Yolları. Yüksek lisans tezi, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Kurt, Necati. 2015. “Alevi-Bektaşi Cemlerinde ‘Deste Bağlama’ Geleneği ve ‘Bağlama’ Adının Kaynağı.” Ege Üniversitesi Devlet Türk Musikisi Konservatuvarı Dergisi 7: 43-62.

Mert, Burak. 2018. Geçmişten Bugüne Yeni Anlatım Olanaklarıyla Bağlama. Yüksek lisans tezi, Mimar Sinan Güzel Sanatlar Üniversitesi Güzel Sanatlar Enstitüsü.

Özdemir, Uğur Umut. 2009. Bir Halk Çalgısının Sosyal ve Kültürel Kimlik Bağlamında İncelenmesi: Ehl-i Hak’ın Kutsal Sazı Tanbur. Doktora tezi, Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Öztürk, Okan Murat. 2007. “Onyedi’den Yirmidört’e: Bağlama Ailesi Çalgıları ve Geleneksel Perde Sistemi.” Folklor/Edebiyat 15 (58): 63-88.

Parlak, Erdal. 1998. Türkiye’de El ile (Şelpe) Bağlama Çalma Geleneği ve Çalış Teknikleri. Yüksek lisans tezi, İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.

Parlak, Erdal. 2000. Türkiye’de El ile (Şelpe) Bağlama Çalma Geleneği ve Çalış Teknikleri. Ankara: Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları.

Yeşil, Yavuz. 2015. “Ağız Kopuzundan Çene Arpına: Türk Enstrümanının İzinde.” 21. Yüzyılda Eğitim ve Toplum 4 (12): 191-199.