Sivas Massacre (2 July 1993)

* This entry was originally written in Turkish.

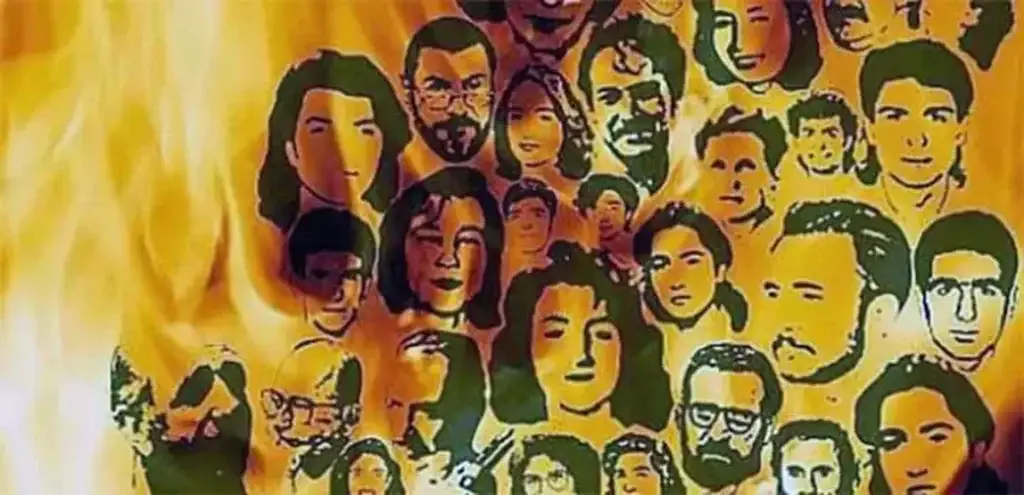

The Madımak Massacre, which took place during the Pir Sultan Abdal Cultural Festival in Sivas on 2 July 1993 and claimed the lives of thirty-nine people—thirty-seven of whom were festival participants—stands as one of the most visible and large-scale acts of anti-Alevi violence in the history of the Turkish Republic. This entry approaches the massacre not as an isolated event confined to a single day, but as one embedded in a broader historical and political context. The early 1990s were marked by political assassinations, internal power struggles within the state, escalating tensions surrounding the Kurdish issue, and a growing public visibility of Alevis—all of which form the structural backdrop of the massacre. The Sivas Massacre represents a critical turning point in which the Alevis’ demands for recognition became subject to intense political contestation and suppression. In the aftermath, politics of denial and impunity were institutionalised through actions such as the transformation of the Madımak Hotel into a restaurant, the eventual statute of limitations on legal proceedings, and symbolic yet hollow gestures of justice. This entry explores how the event has become a “chosen trauma” within Alevi collective memory, positioning the Sivas Massacre at the intersection of struggles over identity, memory, and justice in contemporary Turkey.1993: Political Crises and Social Tensions

The year 1993 marked yet another critical juncture in Turkey’s political history. It began with the assassination of Uğur Mumcu (1942-1993), a journalist highly influential among secular and republican segments of society, who was killed by a car bomb on 24 January. This was followed by the sudden deaths of several other prominent political figures: Finance Minister Adnan Kahveci (1949-1993) in a car accident on 5 February; Gendarmerie General Commander Eşref Bitlis (1933-1993) in a military plane crash on 17 February; and President Turgut Özal (1927-1993) from heart failure on 17 April. The causes of these deaths remain controversial in the public sphere, and segments of society continue to believe that conspiracies were involved.

The same year also marked a turning point in what is often referred to as the “Kurdish Question.” Following the First Gulf War in 1991, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) capitalised on the emergent de facto situation in Northern Iraq and adopted a strategy of intensified armed struggle. In 1993 alone, the PKK carried out 413 armed attacks, resulting in the deaths of 403 security personnel-regardless of whether they were on active duty-and 1,166 civilians, including teachers assigned to rural areas and local villagers.

Amid these deeply unsettling developments, the events that unfolded in Sivas on 2 July 1993 had a profound impact on Alevis both in Turkey and abroad.

The Pir Sultan Abdal Festival and the Escalation of Violence

The 1993 Pir Sultan Abdal Commemoration Festival had its roots in the period before the 1980 military coup in Turkey. The first festival was organised in 1979 by the Banaz Village Hometown Association, which had been founded in Ankara that same year, and was held in Banaz, the birthplace of the 16th-century Alevi poet Pir Sultan Abdal. Following the 1980 coup, the association was shut down but reopened in 1989. In 1991, it was renamed the Pir Sultan Abdal Cultural Associations, and in 1992 it organised the third edition of the festival again in Banaz. In 1993, a portion of the events was relocated to the city centre of Sivas at the invitation of the then-governor Ahmet Karabilgin. However, tensions began to mount before the festival due to the inclusion of renowned author Aziz Nesin (1915-1995) among the invited guests. At the time, Nesin was the chief columnist of the daily newspaper Aydınlık, which had sparked controversy for serialising a Turkish translation of Salman Rushdie’s novel the Satanic Verses (1988). In a 2020 interview, Nesin’s son, Ahmet Nesin, claimed that it was actually Doğu Perinçek who was responsible for initiating the publication of the translation.

On 1 July, following a panel discussion held at the Buruciye Madrasa, Aziz Nesin was confronted by a reporter from the conservative television channel TGRT who deliberately questioned his belief in God. Nesin’s response provoked agitation among the crowd gathered nearby. On the following day-Friday and the second day of the festival-the unrest escalated beyond expectations, leading to the cancellation of scheduled events. Some of the invited participants sought refuge in the Madımak Hotel, where they were staying. The hotel was soon surrounded by a large and hostile mob shouting anti-Republican slogans such as “The Republic was founded in Sivas, it will be destroyed in Sivas”-a reference to the Congress of Sivas held in 1919 as a foundational moment in the Turkish independence movement.

Despite the presence of military units and local security forces in the city, authorities failed to intervene in a timely manner. After hours of growing tension, the enraged crowd set fire to the hotel. Thirty-seven people lost their lives, thirty-three of whom were festival participants, many from Ankara. Among the victims were siblings Koray Kaya (aged 12) and Menekşe Kaya (15), sisters Asuman Sivri (16) and Yasemin Sivri (19), members of a semah (ritual dance) group, promising young musician Hasret Gültekin (22), Dutch scholar Carina Thuys (23), who had been conducting research on Alevism, folk musicians and married couple Muhlis Akarsu (45) and Muhibe Akarsu (44), physician and poet Behçet Aysan (44), and writer Asım Bezerci (62). In addition, two hotel staff and two individuals from the crowd also died during the prolonged siege. The victims’ ages and their public profiles amplified the trauma and public outrage following the attack.

The Shattered Hope for Democratisation

The events of 2 July 1993 in Sivas marked the end of a period of tentative democratisation in Turkey that had emerged following the 1987 constitutional referendum and gained momentum with the Social Democratic People’s Party’s (SHP) significant victory in the 1989 local elections. In particular, SHP’s inclusive approach-which did not shy away from nominating Alevi and Kurdish candidates-resonated with the electorate, earning the party nearly 29% of the national vote. As a result, SHP won control of 39 municipalities, including major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir.

In retrospect, the political climate surrounding SHP’s 1989 electoral success bears striking similarities to the public optimism observed following the June 2015 general elections. SHP carried its momentum into the 1991 general elections, where it garnered 25% of the vote and secured 99 seats in parliament, making it the second-largest party after the Motherland Party (ANAP).

The Geopolitical Significance of Sivas

Numerous books have been published to narrate and analyse the events that took place in Sivas on 2 July 1993. Among these, a book by Muzaffer Erdost (1932-2020) remained relatively obscure at the time, likely because it contextualised the massacre within the framework of a broader political conspiracy. Erdost, a leftist publisher and journalist who founded Sol Yayınları in 1965, was instrumental in translating classic Marxist literature into Turkish. His brother, İlhan Erdost, was beaten to death in the Mamak Military Prison following the 1980 military coup. In his 1996 book Türkiye’nin Yeni Sevr’e Zorlanması Odağında Üç Sivas (“Three Sivas in the Context of Turkey’s Forced March Toward a New Treaty of Sèvres”), Erdost portrayed Sivas as a geopolitical crossroads and sought to situate the 1993 massacre within the changing strategic role of Turkey in the post-Soviet era.

This framing drew on a New York Times op-ed titled “The Third American Empire”, written by Jacob Heilbrunn and Michael Lind on 2 January 1996, which was brought into Turkish public discourse by journalist Cengiz Çandar (b. 1948) in early January of that year. According to the authors, the “heart” of this Third American Empire was composed of the former Ottoman territories that had been absorbed by the Soviet Union or allied with it during the Cold War. The empire’s “axis” was formed by the Middle East and the Balkans, while its “support” and “balance point” was, in Çandar’s view, Turkey.

In Erdost’s account, Sivas is repeatedly emphasised as a “balance point” within Turkey. He contends that various social conflicts aimed at depopulating the urban areas of Sivas, and later its rural periphery to the east (Tunceli to Erzurum) and to the south (Kahramanmaraş to Hatay), of Alevi populations were closely related to the designs of the “Third American Empire” (p.12). The 1978 massacres in Sivas, Kahramanmaraş, and Çorum, as well as the 1993 Sivas massacre, shared a common trait: the dominant reactionary forces sought to pit the progressive and reactionary elements of the working class against one another. While the 1978 attacks were framed as fascist assaults on revolutionary democratic movements exploiting the traditional Alevi-Sunni divide-where most of the victims were Alevis-the 1993 massacre was conducted under the guise of “defending the honour of Islam.” Even so, Erdost argues, the Sunni community’s support for the violence can still be understood through the lens of sectarian tension (p.15).

He further posits that one of the motivations behind the 1993 massacre was to prevent the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) from gaining a foothold in Sivas and thereby opening a route to Samsun (p.17). Referring to an article published in the socialist periodical Sosyalist Alternatif, Erdost highlights two conclusions: first, that Sivas has strategic importance as a junction between eastern and western Turkey; and second, that it holds geopolitical significance as a crossroads for Turkey’s diverse “peoples” (p.29).

He also challenges the claim that leftists “politicised the Alevis,” asserting instead that politicised Islam-in the form of religious orders and brotherhoods-had expanded in tandem with the repression of the Alevis’ secular and democratic identity. As a consequence, Alevis increasingly sought political representation in their own name and on their own terms (p.32).

Alevism, Public Visibility, and the Struggle for Political Definition

Throughout the history of modern Turkey, Alevis have had limited opportunities to make themselves visible in the public sphere. Even in instances where visibility was achieved, it was often shaped by prevailing political upheavals and rarely resulted in tangible gains for the Alevi community. For example, many leftist movements chose to interpret the 1978 Maraş massacre as an assault by “fascists” on “the people,” deliberately avoiding any mention of Alevis. This erasure fostered a deep sense of abandonment among Alevis and generated significant distrust toward leftist groups, especially after the 1980 military coup. During the early 1980s, Alevis entered a period of quiet introspection. In this context, they sought to preserve their culture through music-a central component of Alevi rituals-amid ongoing processes of urbanisation and displacement.

This period of silence was broken in 1987, when Turkey prepared for a constitutional referendum concerning the removal of certain provisional articles from the 1982 Constitution. During this time, the Hacı Bektaş Veli Commemoration Ceremonies-long held as a central gathering for Alevis since the 1960s-began to attract politicians from various parties. These interactions marked a pivotal moment in which Alevis started to be recognised as a political constituency. They gained a new kind of public visibility, one in which their demands could be expressed explicitly and in reference to their distinct identity.

Two special issues published by the influential magazine Nokta, three years apart, reflect this shift in visibility. The first, titled “Alevism is Disappearing into History: The Story of a Religious, Cultural, and Political Dissolution” (27 September 1987), and the second, “Alevis Say ‘We Will No Longer Remain Silent’: Alevi Thought Experiences a Major Revival” (13 May 1990), capture the transformation of public discourse on Alevism. In May 1990, a group of prominent left-leaning intellectuals and journalists published an open letter in the newspaper Cumhuriyet, known as the “Alevism Declaration.” This letter, for the first time, publicly articulated the demand for Alevi recognition in terms of identity politics.

However, this newfound visibility came at a cost. In the face of Alevism’s unexpected public prominence, all major political currents began to contest how Alevism should be defined. Since the founding of the Republic, various political traditions-secular republicanism, religious conservatism, Turkish and Kurdish nationalism-have competed over the definition of national identity. These same traditions have since sought to frame Alevism in ways that align with their own political agendas, and these struggles continue today.

The Traumatic Legacy of the Massacre and Collective Memory

The Sivas Massacre of 2 July occurred at a moment when Alevism had begun to gain notable public visibility. The prolonged siege of the Madımak Hotel, broadcast on national television, provoked outrage among Alevis both in Turkey and abroad. This period saw a rapid increase in the number of Alevi cultural and religious associations being founded. The anger and alienation deepened further on 12 March 1995, when four coffeehouses and one pastry shop in Istanbul’s Alevi-majority Gazi neighbourhood were attacked by automatic weapons fire from a stolen taxi in the evening hours. In response, Alevis took to the streets in the neighbourhoods where they lived, triggering a massive uprising in Istanbul that lasted for three days. Approximately forty people were killed and hundreds injured during this wave of protest, largely due to the police’s excessive use of force. The perpetrators of the initial attack have never been identified. Alevis interpreted these two traumatic incidents-where they were directly targeted-as manifestations of a broader conflict between republican secularism and Islamic conservatism, particularly during a period when an Islamist political party was gaining political momentum. This interpretation echoes how they had previously viewed the political violence they experienced in the late 1970s, which they understood as a consequence of the struggle between right- and left-wing factions.

It is noteworthy that Muzaffer Erdost’s theory of the “Three Sivas 1993” resurfaced years later. In the second half of the 2000s, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) launched a series of so-called “democratisation initiatives,” ostensibly aimed at resolving Turkey’s long-standing human rights issues, including the grievances of Alevis and Kurds. One outcome of this process was the 2010 constitutional referendum. Once again, Alevis found themselves placed in the spotlight by an initiative they had not requested, gaining a form of political visibility that felt imposed rather than chosen. During this period, Alevis hesitated to support the AKP’s reform agenda. As a result, pro-government media accused them of defending the “tutelage” of the old regime, represented by the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP).

On 24 June 2011, just one week before the 18th anniversary of the massacre, the state broadcaster TRT aired a special news segment titled Faili Meçhul (the Unsolved), portraying the 1993 Sivas events as a PKK-orchestrated provocation aimed at exacerbating Alevi-Sunni tensions and destabilising the country. This narrative was novel even for Islamist circles, some of whom had speculated that the massacre was orchestrated by a faction within the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) to undermine the Welfare Party (RP) government. Many Alevis interpreted this emerging discourse as an attempt by political Islam to absolve itself of its role in the massacre and to undermine Alevi claims for recognition.

In an interview published in the pro-Kurdish newspaper Özgür Gündem, a former member of the Turkish Special Operations Department (ÖHD), speaking anonymously, claimed that the Sivas massacre had actually been part of a covert military operation by the TSK intended to prevent the PKK from establishing a foothold in the region. Just three days after the events in Sivas, on 5 July 1993, a group of PKK guerrillas carried out a retaliatory attack on the Sunni village of Başbağlar in Erzincan, killing 33 civilians. PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan (b. 1949), however, stated that he had not authorised the attack and that the commander of the guerrilla unit had made the decision independently.

Denial, Impunity, and Official Narratives

In a period when various political movements-including the AKP-attempted to rewrite history under the banner of “democratisation initiatives,” the continuing debate over what truly transpired in Sivas in 1993 is deeply telling. It illustrates that all major political currents in Turkey are still engaged in a struggle over how to incorporate Alevism into their respective agendas. None have seriously attempted to meet the demands Alevis have voiced for over four decades, dating back to the late 1980s. Nor have they managed-or shown the willingness-to place the Sivas Massacre within a meaningful legal or political context. The Madımak Hotel, which operated as a kebab restaurant for many years following the massacre, was only converted into a science and culture centre in 2011, as part of the so-called “Alevi Opening.” However, most Alevi organisations, both in Turkey and in the diaspora, had long demanded that the site be turned into a museum of shame (utanç müzesi).

In voicing these demands, Alevis pointed to the collective mourning observed in Germany following the 29 May 1993 arson attack in Solingen, where five members of the Turkish-German Genç family were killed by neo-Nazis. They cited this example to show how official recognition and commemoration of tragedy could be meaningfully realised. In contrast, the plaque placed at the entrance of the Madımak Science and Culture Centre merely stated: “On 2 July 1993, thirty-seven of our citizens lost their lives in a tragic incident. We hope such a pain will never be experienced again…”-carefully avoiding any reference to the actual nature of the violence. If nothing happened, then no one can be held responsible. On 13 March 2012, the statute of limitations expired in the Sivas trial for five of the remaining defendants. On 6 September 2023, President Erdoğan used his power of pardon for the second time to release Hayrettin Gül-the primary perpetrator of the massacre-who had originally been sentenced to death (later converted to aggravated life imprisonment following the abolition of capital punishment), citing health reasons.

To this day, Alevis continue to mourn the victims of the Sivas Massacre and organise annual commemorations. Thirty years on, Sivas remains a powerful “chosen trauma” for Alevis both in Turkey and abroad-a formative and defining event in their collective identity.

Conclusion

The Sivas Massacre of 2 July 1993 stands not only as a case of organised violence against Alevis, but also as a striking example of the structural denial, impunity, and politics of suppression faced by communities struggling for recognition in Turkey. Even after three decades, the massacre retains a central place in both collective memory and public discourse. It continues to serve as a symbolic anchor for the Alevi demands for justice, recognition, and equal citizenship.

Ata, Kelime. 2021. Kızıldan Yeşile: Sol, Aleviler, Alibaba Mahallesi ve Sivas’ta Dönüşen Siyaset. Ankara: Turan Yayınevi.

Çaylı, Eray. 2022. Victims of Commemoration: The Architecture and Violence of Confronting the Past in Turkey. New York: Syracuse University Press.

Ertan, Mehmet. 2021. Aleviliğin Politikleşme Süreci: Kimlik Siyasetinin Kısıtlılıkları ve İmkânları. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları.

van Bruinessen, Martin. 1996. “Kurds, Turks and the Alevi Revival in Turkey.” Middle East Report 200: 7-10.

Yıldız, Ali Aslan, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2011. “Inclusive Victimhood: Social Identity and the Politicization of Collective Trauma among Turkey’s Alevis in Western Europe.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 17 (4): 243-269.

Zırh, Besim Can. 2015. “Euro-Alevis: From Gastarbeiter to Transnational Community.” In The Making of World Society: Perspectives from Transnational Research, edited by Remus Gabriel Anghel, Eva Gerharz, Gilberto Rescher, and Monika Salzbrunn, 103-132. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Zırh, Besim Can. 2024. “Görünmezlik ve Tanınma Arasında: Sivas Katliamı.” In 100 Kesitle Cumhuriyet Türkiyesi’nin 100 Yılı, edited by Alp Yenen and Erik Jan Zürcher. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları.

Zırh, Besim Can. 2023. “Yadsımanın Nesnesinden Tanımlama Mücadelesi Öznesine Alevîlerin Uzun Onyılı: Seksenler.” In Türkiye’nin 1980’li Yılları, edited by Mete Kaan Kaynar. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları.